Boatrides, Thongs, and New Books

Parenting is vulnerability and there's nothing we can do about it.

I am still, somehow, “vacationing” in Massachusetts. This week, my son and I took “90 West” (in Boston we do not say the word “the” before our freeways, and on second-thought I think we don’t call them freeways), from my parents’ apartment in Cambridge to Western Mass, to visit one of my oldest friends. I couldn’t connect my phone to our car’s stereo, so, in an act of extreme benevolence, my son permitted us to listen to my old CDs. We played Frane’s Fantastic Boatride, a trippy, 15-year-old electronic album about getting really, really high, and imagined we were jaguars slowly prowling through the jungle. At the Ludlow Service Plaza, he spent his own money playing Crusin’ USA and didn’t whine about how quickly he died. I won him a plastic duck from the grabby game, that we understood to be dressed like an astronaut. For whatever reason, I am a tad self-conscious about what a nice time we had—whenever a parent gives the impression that things can go smoothly, it makes me throw up in my mouth a little bit.

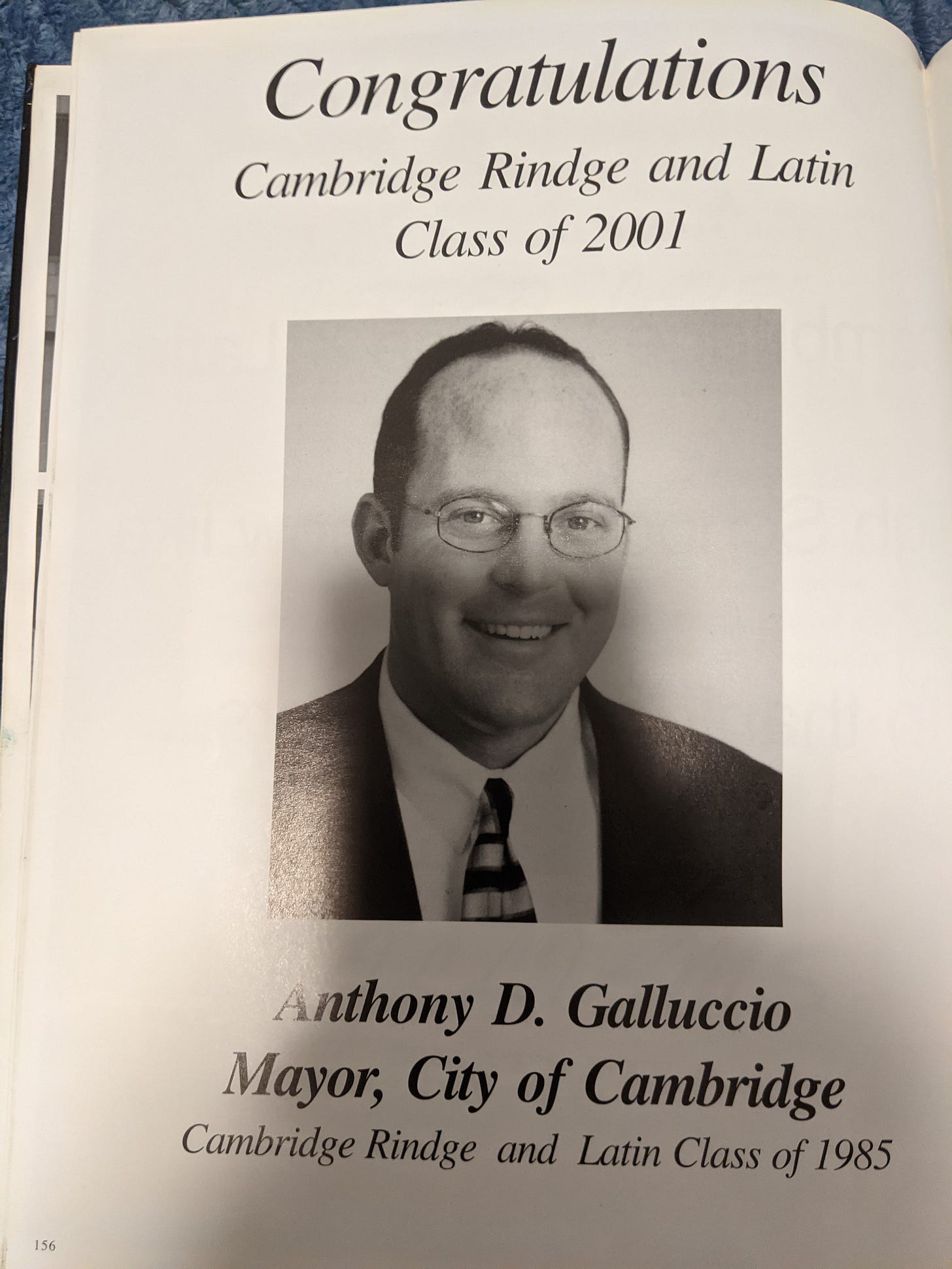

After the kids were safely tossed into their sleepless beds, and I was on my infinity-and-a-half glass of wine, my friend unearthed our high school yearbook from her basement. When was the last time you looked at your high school yearbook, friends??? There were too many pictures of me, but also not enough, and the feelings I felt for so many of my hundreds of classmates came rushing back to me, like a yellow Cruisin’ USA jeep smashing into a computerized mountainside. There were proms and theater productions and baby tees and so many different hair colors, all mine. There was Mayor Galluccio, who everyone called “The Gooch,” and who was later sent to prison for fleeing the scene of a car crash and having alcohol detected on his breath, which he blamed on toothpaste, wishing us a happy graduation by singing a spoof of Sisqó’s Thong Song (true story - I am not talented enough to invent something that good).

What amazed me, even more than how well I remembered The Gooch’s awful lyrics (“Look at all these graduates, you know Cambridge can’t handle this….So long long long long long!”), was just how incredibly vulnerable a time this was. All the hours I spent worrying about how much prettier Alyssa Tingle was (a lot), whether some boy whose mother still bought all of his clothes wanted to meet me under the overpass after school. And, even though it was before the age of social media (I do not consider the single AOL chat room that existed to fall under that category), it was all so public. When Alex Brown cheated on me with my friend freshman year, and then I cheated on him weeks later, we aired our grievances in shared spaces. A punch was thrown through a glass door in school hallway, profanities were screamed, all in view of our peers. We took it so, so personally. When Alex and I finally broke up, word got to me that his friend had come up with the witty diss “What do you get when you slap Sarah Wheeler in the face? A fistful of make-up!” I still think of that and feel my heart sink. Ouch, ouch, ouch.

In our senior theater seminar, in true high school theater class form, we had to perform a vulnerable act in front of one another, in the service of building trust. One kid who hated his singing voice sang a lullaby, some people told secrets, at least three students showed us their abs. I stood in front of my classmates with a packet of baby wipes, slowly taking off the heavy face of concealer that was my school uniform, and sobbing. Good. Grief. But also, yes, of course. Those were the times.

I have been thinking about this vulnerability, and how it has found me once again as a parent. Many parents first encounter it even before they have children—fertility challenges, miscarriages, pregnancy concerns that turn out to be nothing or, at times, something. Whatever god gave me terrible skin (still!) made it up to me by granting me a pretty easy pregnancy. I felt the opposite of vulnerable when I was pregnant with my first child—superhuman, impervious, shiny-haired. But in the weeks and months after having him, I found myself completely shut-down. It wasn’t depression—it was terror—the realization that I’d made myself very vulnerable to pain, loss, rage, disappointment—and that there was no going back.

Before I was a parent, as a school psychologist, although I considered myself to be an empathic person, I could not understand why some parents behaved so badly. A dad made threats and stormed out of a meeting. A mom told me I was a terrible, terrible person, and since I had not yet learned how to separate others’ happiness from my own worth, this made me feel terrible for a long time afterwards. After having kids, I felt privileged to see people like this, so vulnerable, when most of the time they walked around acting like they had answers or looking put together. They were just victims of the ultimate vulnerability, like me. Parenting cut them down to size. In public, and mostly on social media, some of us perform steadiness, others perform vulnerability, a select few really and truly are vulnerable. It’s a lot like a high school theater exercise. I would imagine that any parent who watched the Britney Spears documentary, who saw her being gaslit for wanting to see her own children, 100% got why she smashed that paparazzo’s windows with an umbrella. I was surprised she didn’t kill him.

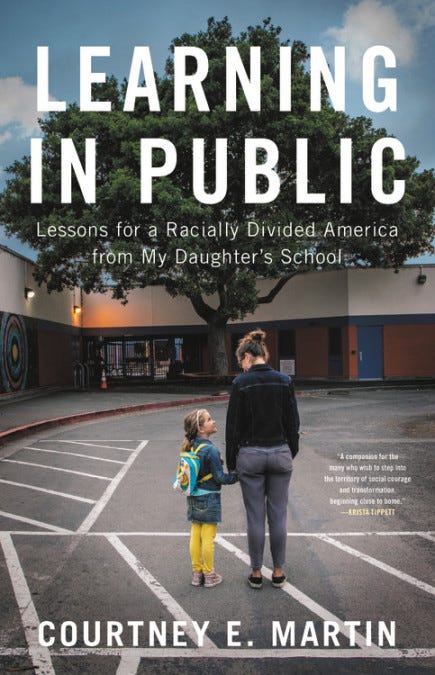

This past week, I have been thinking about friends, and vulnerability, and parenting, and public displays, and I have also been thinking about this one book that includes, majestically, all of these things. You see, my friend wrote a book. And I don't say this in the way someone might tell you, “my friend read his 90-minute poetry cycle about his dog at the Friday open mic at our local game store.” Because my friend happens to be a celebrated author and journalist, and this book is kind of a big deal. I had the immense honor of reading it a few months ago and afterwards I did something that I have never once done, after decades of consuming and loving books, which is, upon finishing the last page of a book, to close it, look at it lovingly, and then give it a kiss.

This is a book about school integration, yes, and it is important because it will spark much needed debate on this topic, one that is dear to my heart, mostly because I am lucky enough to have lived across the fence from Courtney for many years. But it is also, at its core, a book about the vulnerability of being a parent. It is a public display of actual vulnerability as well as a challenge to us parents about the ways we try to correct for this vulnerability, sometimes at the expense of ourselves and our children.

When wealthy parents, often of White children, tell people that we are sending our children to a public school that has poor test scores and few White kids, we often hear responses like “Don't you want the best for your children?” “Why would you make your child into an experiment?” And, “Why are you making this so political?” Courtney makes great intellectual and sociological arguments in response to all of these questions, but what she shows us, through scenes of her own parenting, is even more powerful. All parents want the best for their children, to keep them safe and make it all feel a little less vulnerable. But the actions we take in service of that (get our kids into the ‘best’ school, buy into the ‘safest’ neighborhood), which we tell ourselves are reducing the vulnerability of ourselves and our children, are false idols. I know many, many children who have suffered at well-regarded schools. There are just so many things that go into having a happy childhood.

Keeping our children from potentially harmful experiences, or ones that we have been told by other White parents on the playground will be harmful, is just one very narrow definition of being less vulnerable. But Courtney’s book shows us that reducing vulnerability may not be the goal of parenting. It is by leaning into the vulnerability, accepting that it will never go away, and knowing that if this is the case, we might as well show our children how much are making it up as we go along, we might as well tell them the truth, that life is about never being certain and in light of that, we have decided to move forward with love and humility and in community and we hope they will move forward with us, though we know how they turn out is mostly out of our control. Every child is an experiment. Every choice we make for our children is a political act. The best thing is the thing that makes us feel more human, and if our kids can pick up on that, well, bonus points.

I have had many of my most vulnerable parenting moments in Courtney’s presence. I have been unnecessarily mean to my children and unnecessarily defensive of them. I have screamed, sobbed, self-medicated. I once left my children watching television in my house, knocked on her door, and asked her husband John, without a trace of humor, whether he would testify in my defense if I murdered them. It is very moving to me, then, that Courtney has chosen to share her vulnerability as a parent with the world, with anyone who reads or listens. This is not a performance, and it is not perfection. It is an ode to the uncertainties of being alive and responsible for others’ lives, and I think you will love it as much as I, not too long ago, really and truly loved Alex Brown.

Order Courtney’s book, Learning in Public, today, and attend one of her many book talks with interesting people over the coming weeks.

Coda: I visited Alex Brown at his bar in Cambridge on Sunday. We are now, I am happy to say, friends.

Also, this:

-Spending time with my nieces means I’m more up-to-date with the culture than I was a month ago. I finally got around to listening to Olivia Rodrigo’s new album, and it is “all that and a bag of chips,” as I would have said at my niece’s age, and this song, which is very 90s and very adolescent, is fabulous and fitting for today’s theme:

Loving all of this. Because of course. But also because get out of here with Frane’s Fantastic Boat Ride, which I bought on vinyl from Amoeba in 2001 and still feel very high when listening to, even if the only substance I’ve consumed is seltzer.

Big vulnerable heart swells for this post. I found you via Courtney's newsletter and I'm so happy I did. It's lovely to see your parenting friendship in action. Looking forward to reading.💗