This past fall, my son became obsessed with lemonade stands. We have a lemon tree in the backyard, which I thought when I moved here 20 years ago was peak exotic, but it turns out is a somewhat boring fact of California life. When I spent a weekend as a “prospie” at what would be my future college in the Inland Empire, I saw a boy, who felt like a man to me, reach his hand out of a dorm window and produce a lime for gin and tonics. This, I believe, was the moment I decided not to go to Oberlin, where no one smiled as they squeezed citrus into your drink, like a bonafide mixologist, and where a top-layer of hopelessness enveloped even the parties.

We produced lemonade, which my son often reminded me involved little to no overhead, both Saturday and Sunday on one warm weekend. Each day we changed our signage, our strategy of where to place the table; in front of our house on a side street (dud) or right on busy Telegraph Avenue (better). Eventually, he noticed that the head shop across the street seemed to get the most foot traffic, (“Mama, that place is famous!”), so we (I) dragged our table, chair, sign, tape, cups and pitcher, to the sidewalk outside, where the door chimed with every in-and-out. I don't know what it is like to live in the suburbs, but for me, sitting on a city street next to my son's lemonade stand is the most validating experience for our urban location choice, the occasional needle discovery be-damned. Every kind of person you could imagine came to the lemonade stand, and their responses were unpredictable. Smiling or slightly annoyed, incredibly generous, the guy who pulled over in his car, beckoned to my son, handed him a fistful of change and said “I don't need any lemonade, I just respect the hustle.”

A young couple walked by on the way back to their car, hospital visitor stickers on their chests. They overpaid for a glass (we charged a quarter or, upon my insistence, offered it free to those who did not have change) and chatted with us briefly in what started as English and quickly shifted to my stilted Spanish. After we said goodbye, the man, depositing his companion in a mini-van, doubled back towards us. He approached me, and asked in a lowered voice, why I would do this with my son, this lemonade stand. Though the lack of nuance in my language made me unsure of exactly what he meant, I told him my son had asked for some toy, and I’d replied that he was welcome to find a way to buy it for himself. That it taught him to be a little more outgoing, this hawking of wares. That we liked being out in our neighborhood and also we were pretty bored that weekend and I wanted my son to understand that it was okay just to give something way, too. He listened attentively, like I was giving a very coherent lecture rather than a fragmented list of under-developed parenting choices, littered with grammatical errors. He thanked me and explained that he and his wife had just visited their son, born 11 weeks early and still in the NICU after several months. He wanted to know, he said, what it was like to be a parent of a big kid like this, what he had to look forward to. He needed some hope, grandiose or mundane, that his son would grow to be someone he could spend a Sunday afternoon doing something like this with, that his son would want things he could give him but would choose not to for his own good, that he could teach his child lessons about life, likely more intentional than mine.

It has been a rough week, friends. Many are saying we are back in something, but also the flavor of it is something new, if only in how exhausting it is to do the same thing over and over again, this panic, this despair, this cancelling of plans. It’s not exactly that I’m worried everyone I love will get covid, though more people that I love have gotten it in the last week than in the last year and a half combined. It's more that I am low on hope. It’s not just the coronavirus-of-it-all, but that the hopelessness is pounding at us from many different angles, personal and political, global and local.

I feel pretty certain that my children are the only thing keeping me, at the moment, from an all-consuming depression. But the whiplash of toggling back and forth between my own pessimism and the bright-eyed outlook of my progeny is sometimes too much to bear. When we found out last week that an unhoused, unwell man who had been a neighborhood fixture for years was killed, by another unhoused person, just two blocks from our home, I cried quietly in the living room. My five-year-old son found me there and said “I’m sorry you’re so tired, mom.” When I told him I was tired, but I was crying because I was sad, explained to him that this man, who we knew by name, who we often fumblingly tried to explain to our children that we should both keep our distance from and somehow communicate love to, had died, he wrapped his arms around me and assured me that it would be okay, his spirit was still with us. What was his spirit like, anyway, these last tormented years, cycling in and out of jail, stalking his completely overwhelmed mother, who was our neighbor, like he both wanted to hurt and protect her? How could this be all that was available to someone? How could this, also, be mothering? My son had thought I was sobbing from exhaustion. I suppose I was.

My husband believes we are grieving a world our children will never know. They cannot be nostalgic for what they never experienced. The world I miss, also, was never really there, certainly that was understood by the many many inhabitants of earth who have never felt that the world was designed to keep them safe and give them opportunity and tell the truth, which I guess, if I am being truly honest, I did once believe, even after I was no longer a child. Perhaps I have always had more hope than was necessary, many survive on very little, or conjure hope with very little evidence of its ever proving warranted.

I have been somewhat obsessed with watching a movie every single night of this vacation. I don’t think I’d watched one in months, but when I do things, I usually do them at a loud volume, and I aim to keep this streak going as long as I can. I'm so behind on things I want to see, and now that I've broken the seal and know that I can stay awake for two hours if I really want to, it has become a compulsion, an enjoyable one at least. Watching can be a means for avoiding hopelessness, the way my husband and I shuttle ourselves to an episode of British Baking Show to avoid our individual and collective despair about what happens in the two or sometimes three hours between when we put our children to bed and when they actually fall asleep. But of course, making or consuming art, and some would argue that even the Great British Baking Show is art, is an act of hope. We have watched seven movies now, some fabulous, some terrible, without consistent agreement about which are which. I can’t believe how all of these people put their ideas and skills together into something I could view from my couch. When it is done well, I am deeply moved. When it’s bad, I am amazed that not everyone in the entire world wants what I want. Watching these stories, I have felt hopeful, for what, I don't know, but I feel it still.

On the last day of school before Omichristmas break, I chaperoned 50 Kindergarteners on a field trip to see a dress rehearsal of the Nutcracker at Oakland’s art deco Paramount Theater. I don’t really understand why people love Disneyland and/or World, why it delights and enchants and entertains them, but I imagine it must feel to them what being around 50 Kindergarteners feels like to me. I love every minute of it—their brilliant and nonsensical observations, their enormous backpacks, their runny hoses, their insipid competitions. When we finally made it to the theater, despite the impossible slowness of all of those little legs, the constant stops of the city bus, the pausing at every corner to count heads, we were early. We sat in the semi-dark for what felt like hours, waiting for what I knew would also be an endless performance to begin. “I think we live here now,” one little girl spoke into the darkness. But still, we stared up at the ornate ceiling and told stories and snuck bites of granola bars (I am a rebellious chaperone). When the rehearsal finally began, the director barked at the dancers over the PA system, scolded the audience of small children for clapping at inappropriate times, said things like “show us your beautiful smiles, ladies!” My friend and I made eyes at one another. What a douche. My son defended him, said he was just stressed. But we didn't hate the director, we pitied him. We had something he didn't have; we understood what this whole thing was about. We were exhausted, we were bored, we were touched and exhilarated, by the people who had restored and cared for this century-old building with likely little reward, by the live music and dance, by silly little human things like when an Adonis of a man, who could pirouette with perfection, forgot to take off his mask as he spun on stage, blue-faced. We emerged from the darkness what felt like years later and I almost couldn’t believe we’d gotten to do that, be entertained, with all the imperfections, together. We held the disgusting hands of the children, who had touched everything they could see, who still had it in them to play “I Spy” as we made the excruciatingly slow journey back, and hoped.

How much hope do we need, really? How much is enough, and, enough for what, exactly? Just enough to want to see things through? Is hope the two-pound box of See’s candies my husband bought me, because he knows just what I want? Is it laughing about how horrid the ones with fruit in the center taste, every time, but I will still eat them? Is it singing Good King Wenceslas in a room with twenty people and a roaring fireplace, and no one getting sick? Is it saving money? Spending it? Having it at all? Is it enough hope that New York schools are opening next week or that Alabaman Amazon workers are getting another chance at unionizing? Is hope my daughter flushing the toilet and turning to me and saying “Mama, you’re the best news of the century!” It is teaching my son to be less of a jerkwad or withstand a death or calculate five factorial? Is it the PSA for mental health awareness that just came on after the end credits of Friends? Is it enough that young people adore Friends, such a stupid show, even though they know how bad things really are? Is hope saying to your children, maybe not out loud, maybe while they are taking literally everything out of their drawers, scattering clothing and wooden beads and errant playing cards in every corner of the apartment, “you wont love the world I loved, the one that I am kicking around our home every day in a small funk, mourning. But you will love something”? I hope you find enough hope this week to tend to things, or that if you stop tending, you stop dramatically, so that you can feel the difference.

Also, this:

Art Stuffs:

-I just finished a fabulous book. I wish for you to not look up anything more about it (spoilers could hurt here), buy it from a place that does not treat its employees like meat sticks, read it fast and hard, and talk to me about it.

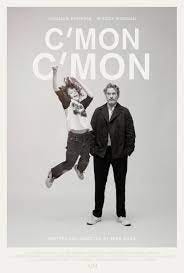

-This movie just really did it for, number one of the seven. It is also perhaps the most entertaining and truthful way to learn about great parenting that I’ve seen.

-This album is giving me company in my sad self-seriousnessness right now. Really beautiful.

Dear Sarah, I love this essay. It really gave me a window into your experience as a parent during COVID, heartwrenchingly so. I can't stand it that your kids might never experience the world you did growing up. But I love your suggestions for entertaining hope--they helped old me, too. Much love to you.

Wow, this one took my breath away. Sort of reminds me of Far From the Tree. Every generation has to reckon with the gap—progressive or apocalyptic—between parents and children. It makes the little ones most intimate to us feel like they live now and will forever in a strange land. So disorienting. So scary. Maybe so freeing?