This Sunday, The New York Times Magazine published a long article by journalist Paul Tough (I remember as a baby teacher reading Whatever it Takes on a plane and being ALL IN) about what is behind the surge of ADHD cases in the U.S., whether stimulants actually work, and whether we really know what we think we do about ADHD.

By the time my alarm went off at 9 west coast time (and after about 30 minutes of customary snoozing), my inbox was filled with links to this story.

Why? Because I assess and treat ADHD for a living. Because I also have been diagnosed with ADHD — something that has been both life-saving and has inspired the kind of skepticism that I’ve had for a long time as a professional. Do I really have ADHD? What is it, even? I wrote about that experience in a piece that has 8000 views, the most for lil ol me!

Call Me By My Name

It took me a year to write this essay. I promise it wont take you that long to read it. I thought this was the place it needed to be, though it departs from my usual form. I’ll be back next week with something a bit more pithy (at least by my standards), but if you’re down for this long-reads cause, I’m so grateful for your eyeballs and brain cells spen…

And because I have strong opinions about it all — opinions that I was delighted to see expressed with Tough’s articulate writing and supported by his research — that ADHD is far from a binary, the diagnosis is highly subjective and criteria is arbitrary, that we throw meds at kids just a little too hastily for my taste.

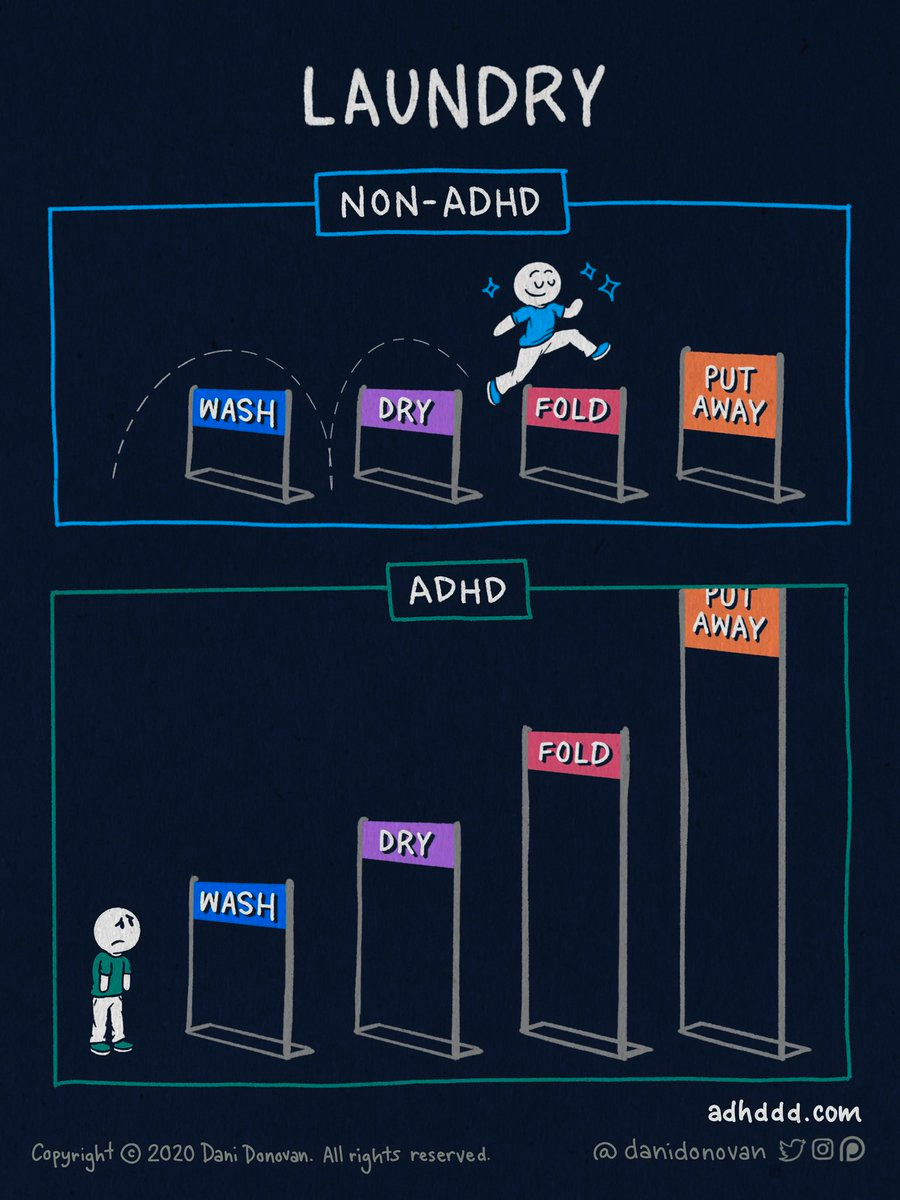

I think Tough did a great job articulating these tensions. We don’t know as much as we think we do about the ADHD brain! Drug companies encourage us to overplay the benefits of stimulants! People with ADHD do differently in different environments! (I would argue with Tough that this doesn’t mean we DONT have ADHD when we’re in the right environment, it just means that our ADHD brain isn’t IMPAIRED). You can read the whole piece here.

If Tough had had a few thousand more words, he might have talked about what treatment actually looks like when it takes the environment into account, and doesn’t blame a fixed brain disorder for people’s life challenges. There is actually a whole world of what is called “neurodiversity-affirming” practicioners out there — therapists, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, etc. Some of us dislike meds, others support people taking anything that makes them feel more like themselves, and less ashamed. But what we all specialize in is trying to make those positive shifts actionable — working with adults and children (often in conjunction with parents and teachers, as children have even less control than the rest of us do over life circumstances) to reduce the pain of someone’s neurotype and increase the joy.

In this model, it doesn’t really matter how much you are “impaired” by ADHD and whether you meet 5 criteria or 6. If that’s how you feel your brain works, and it causes you good times and bad times, you’re a good candidate for the highly accessible, meds-free work of trying to figure out how to find the people, spaces, systems, that work for you and avoid or workaround the ones that don’t. What we’re looking for is what Thomas Armstrong would call “positive niche construction” — creating environments that fit your brain, that play up its strengths and support its weaknesses, that are inspiring instead of shaming.

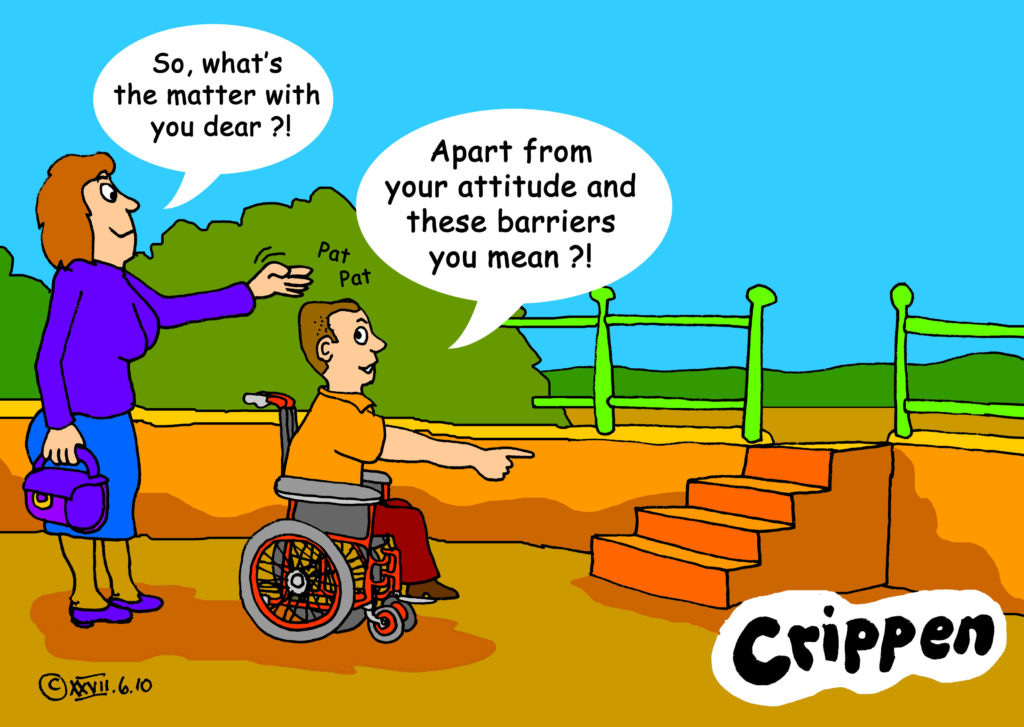

Though there are more ND-affirming practicioners out there than ever, one thing Tough fails to mention is that this idea is by no means new. Disabled academics and activists have been articulating what is called the “social model” of disability since for half a century. Below is a great explanation of this model, which came from disabled academics and activists, and positions disability not as something in the individual that needs to be cured or fixed, but as a mismatch between an individual and their environment. I, for one, am not disabled when I can move around freely and even multi-task while I learn (the Zoom chat feature has been huge for me on this), but I am disabled when I have to sit still and just listen (spoiler alert, I’m not really listening!)

The research I’d love to see, which was not discussed in Tough’s article, is the impacts of ADHD and its various treatments on the people around the ADHDer. I am not fully cynical about why us educators want kids to go on meds—but I have been a teacher of many ADHD students and I can tell you that it often makes our jobs easier. It’s hard work to teach many an ADHD kid, even when the rewards can be great. Hinshaw and Shefflers’s research in The ADHD Explosion showed that states who adopted high-stakes testing earlier had higher rates of childhood ADHD diagnoses. Their theory was that, with more pressure to perform in ways that don’t fit well with ADHDers (test prep is SO BORING), those with ADHD were more impaired, leading to them being identified, and also maybe those without ADHD, or with ADHD-like brains, seemed more impaired too. With real consequences for schools on kids for doing well on tests, the incentive to treat was higher. All of this exists in such complex systems, it is almost impossible to say we make choices for this or that reason entirely.

I am not in any way blaming teachers, constrained as they are and influenced by the same culture the rest of us are in, for the supposed over-diagnosis or over-medication of ADHD. But it does make you wonder if the environmental theory, especially for children, requires some time, energy, and money put into environmental changes! Kids, after all, cannot simply go into a different field. They cannot work late at night and sleep in the afternoon because that’s better for their internal clock’s productivity. In the college for all age, we did away with so many vocational programs that might have been a better environment for some ADHDers, albeit only older ones. We don’t fund GATE programming consistently or effectively. Chidren and adolescents often have, often very few options as far as environments go. And very, very few resources go into helping teachers provide them with them.

And what of parents? An oft-cited statistic is that parents of ADHD kids are much more likely to divorce than parents of non-ADHD kids. Does that change with medication? What about better environmental fit? I would not want to drug my child solely for my own benefit. But also, I am a person, too, with her own life and mental health and regulatory system, and I can tell you after two decades in the field that some children are easier to parent than others. I am not saying it is more worthwhile or satisfying or important to parent some children compared to others, just that some kids go to sleep at night and others don’t, for example. Some experience incredibly intense emotions that, though they come by them honestly, are very difficult to witness, support, and regulate yourself through. These kids are my life’s work, but it would be insane to ask a parent to never consider an option that reduces this difficulty, which seemingly, in many cases, also makes things easier on the kid.

What Tough definitely didn’t say, which people in large media outlets rarely say, which is why I’d rather read more meandering shit from other Substackers, is that we’re all just people fucking doing our best, and also, most research is bull shit. People (Tough, I think, is a bit guilty of this, as am I at times!) often spend whole articles debunking some research, then going “but this one study of 25 people tells a totally different story…” I’m all for using conflicting findings to complicate things, but let’s not swing from one thin idea to another. Even better, let’s just admit that we’re all, always, making it up while we go along.

Sincerely,

From my definitely-maybe-who-cares ADHD brain to yours :)

I just went and read the article you referenced about receiving your ADHD diagnosis and I just want to say - it is one of the best articles I’ve read on Substack. I laughed (the Adam Levine v neck analogy cracked me up) and cried. I can relate to your story so much as a lawyer who thrived in school (except I never did the reading and was always incredibly stressed out), but hit an absolute wall when my career required me to write boring stuff and bill boring hours in a desk all day, and then hit an even bigger wall when I started having kids. I really appreciate your perspective about environment and that resonates so much with me. I tried adderall and didn’t love it. What’s worked better for me is accepting my limitations and restructuring my job so that I do a lot less of the boring document drafting and a lot more time talking to clients. It was hard to admit to myself as someone who has always been really ambitious and competitive that I just really really suck at sitting in a desk all day and billing time, but also why shouldn’t that be hard for me? I also can’t carry a tune to save my life and I’ll never be able to touch a basketball rim at 5’3”, and yet I’ve never felt shame about the genetics that make singing and playing basketball particularly hard for me. It’s interesting how we moralize certain limitations as lazy in our society and accept others as acceptable and unchangeable. Having a diagnosis to point to a few years ago was helpful in helping me unpack the shame I felt around my limitations, but over time as I’ve healed I’ve also felt like the label is less important as I’ve accepted the idea that I thrive in certain environments and don’t in others — just like every single person on this planet!

I have a son who has literally all of the “classic” ADHD traits (constantly getting in trouble with teachers and coaches for his hyperactivity and impulsivity) who is getting evaluated by a psychologist next week. This article has given me a lot to think about, especially with regard to medication. I look forward to reading some of your other posts. I can tell you really, really “get it.”

Really enjoyed this article! As an adult currently going through my own grownup ADHD diagnosis with a 4.5 year-old who is also showing a lot of signs, I can really relate to the part about environmental factors. I think a lot about how navigating late stage capitalism as a self-employed person with small kids has made it feel a lot more difficult for me to organize myself and manage symptoms in recent years that I used to feel pretty on top of. Chaos in the mind begets more chaos.

I also appreciate you shouting out that different kids might need different things. A big goal with my diagnosis is simply to understand my brain better… so that in time I can hopefully help my daughter to find the right environmental conditions to suit her own mind.