I had a birthday this weekend. I bought myself a bright green sweatshirt with tigers on it. Despite my therapist’s warnings that it was a bad idea, I got a tattoo. My husband gifted me the new Aaliyah biography, and I listened to her final album, One in Million, while baking myself a very serious chocolate cake with caramel, which I somehow managed not to burn.

In Afghanistan last week, it appears that a U.S. drone strike killed seven children in one family. Hurricane Ida knocked out all of the power in New Orleans, a city I last visited in 2019, when my youngest was just a baby, where I biked around with an electric breast pump in my backpack, dumping out milk every few hours in the bathrooms of bars. My eighteen-year-old niece is settling in to her New York City dorm, while the subways flood with water.

I am 38. I feel old, but also, unbearably young. My kids are really just babies, my life plans are just kind of sort of starting to finally take a very nebulous shape. I am not quite sure, though, if I am one of the ones who has many, many more years left to go in my human body, how I will keep up morale.

In Oakland, we had out first “orange” air day of the season, as the smoke from the fires to the North finally bested the bay breeze. We went for a “nature walk,” which is how my husband and I refer to hikes with our children, so we are not disappointed that there is little forward movement involved. Every once in a while my eyes would sting, and I would glance over at my kids and think, am I proud that they are moving their bodies up a hill with only minimal whining? Terrified of what this air, which is supposedly not good for “sensitive groups“ is doing to them? Or both? This is how the smoke gets you—acclimating you to its poison bit by bit until you just kind of grit your teeth and let it have its way with your body, like a man you are just too damn tired to keep turning down. Will we just give in to two months of breathing hazards every year, until it becomes three, or twelve? And how old will I be when my kids first ask me the question, “Why did you think this was okay?”

Inside, domestic life putters on. My son is five-and-a-half. He goes to school for big kids, passes other children in the hallway, which in California is usually just, outside, who are already going through puberty. He can multiply five times thirty, and understand that commercials tell us stories about the fabricated joys of consumerism and not, in fact, the truth. He is so unbelievably capable. But he cannot, or perhaps will not, wipe his own ass.

My husband and I have talked, at great length, about whether we are enabling him, and how to break the cycle. Jon makes him do one wipe, just to get used to it, and then comes in for the aftermath. I make up my mind, time and time again, to thoughtfully coach him, to empower him to take charge, quite literally, of his own shit. But then every time he says “please mama, one last time” I go “oh, fine!” and resentfully take care of it for him, with some small part of me relishing being of use.

I have learned through casual conversations at the creek next to the Sunday farmer’s market, which has been dry for years now, but which children like to congregate and create chaos in, that this is a common problem in our demographic. My friend Chris, who manages to make parenting a son seem like one long, raunchy buddy comedy, consulted us on the ass-wiping issue. Her son is eight, and has graduated to the wiping of his own ass, but it didn’t happen overnight. Chris took a deep-end-of-the-pool approach to this — announcing one day that it was time for him to take responsibility, to sink or swim, butt-wise. He started out incompetent, as we all do, and often complained of that uncomfortable feeling one gets when they have not wiped thoroughly, a phenomenon the two of them dubbed “punch butt” because of its making you want to punch your own ass to stop the itching. Eventually, motivated by not wanting to experience punch butt, her son learned to wipe better. And that was that.

Psychologist Madeline Levine, author of Teach Your Children Well and The Price of Privilege, cautions us that excessively helping our kids can end up harming them. Levine advises parents to stop overparenting, and let our children “savor the experiences of being challenged.” I distinctly remember a story she told, on a public radio program, about a mother who realized her third grade child had forgotten their homework in the car. How does the small act of turning the car around and delivering the homework, or of not, cascade into something bigger? Levine pressed listeners to resist the urge to bring the homework—insisting that the stakes are never as high as we imagine them to be, except in the realm of missing an opportunity to take care of one’s own mistakes.

I especially appreciate Dr. Levine’s bent, as she not only teaches privileged parents to stop “parenting for success," but also challenges people to stop thinking only of their children as the unit of change, but also themselves and the lives they’ve created as perhaps in need of some work. When I was an intern in the schools in Tiburon, a town in wealthy Marin Country, north of San Francisco, that is 88% White and has a median home value of over two million dollars, much of the school staff considered Levine to be the second coming of Christ. We used her philosophies, and, more importantly, her data on adolescent anxiety to convince the parents we worked with to let their children fail more. A friend told me the other day about a scandal, which was actually conducted completely in the open, that involved the systematic defunding of the public school in one Marin city, which mostly served Black students, in favor of a majority-White charter school. The district has now been court-ordered to integrate, but in a town like Tiburon, you can safely avoid such things. Does it really matter, I wonder, if you listen and read and attend workshops and slowly learn not to clean up all of your child’s messes for them, if the culture you’re creating for them, or not fighting against being created for them, is completely deplorable?

The challenge of this pandemic, for parents, has been, how do you muck through the mundanity, the dishes, the sibling squabbles, the “I want my corn back on the cob" times, with an occasional smile on your face, when the world around you, and also as a result, inside of you, is spinning out? Many of us managed to cope, in a way, but the trick of it now, eighteen months out, is that the mirage of okay-ness inspires even more dissonance. Kids are back in school-ish, you can eat in a restaurant-kinda, you can see grandma-under certain conditions. But things are not okay, not even for the people who think things are okay. Things are really quite bad, and the world requires our full attention. But also, I want my kids to stay in their beds at night after I put them there, and I think I need to try another kind of detangler for my daughter’s rat nests, and what if we folded sweet potatoes into their mac n’ cheese, would they notice? Or is trying to hide vegetables going to give them an eating disorder? I could figure these things out a lot more easily if the voices in my head would stop shouting “we’re all gonna die some day, who the fuck cares” just for, like, a second.

Levine is now writing more and more about parenting in “modern times,” about how uncertainty leads to anxiety, and our anxiety places an unfair burden on our children, who still need hope. In many ways, I think modern times actually make me a less anxious parent, less under the impression that controlling my child’s environment as much as a I can is worthwhile. But perhaps continuing to focus on the insular decisions of raising children, whether to put them to bed earlier, the thing about vegetable deception, is a form of hope. Perhaps if I spend more time actively scaffolding ass-wiping for my son, letting him “savor” this challenge, it will be a sign to him that I believe the planet will survive long enough for him to say, as a grown man, “I’m so glad my mother taught me how to take care of myself.” But it is very hard for me to believe that this is true. I think it is more likely, then, that I will just continue to wipe my kid’s ass for as long as I possibly can, until the smoke chokes out the sun, and the rising seas overtake us, and we are pulled under, together, in this act of maternal overbearing. Or, even better, maybe we will be covered in ash, fossilized, like the citizens of Pompeii, preserved in an eternal enabling tableau, hand between butt cheeks, forever. And future generations will discover us, and try to make sense of what our final moments said about our lives, and maybe a robot archeologist will write a book about how ancient cultures were in fact quite coddling of their young, and maybe there was some wisdom in that, and perhaps they should consider supporting the hardware of baby robots a bit longer before shipping them out on inter-galactic assignments.

There is a recall election in California, in two weeks, which is small potatoes by some measures and catastrophic by others. It is a stupid thing allowed to happen because stupid people want power and other stupid people are not taking threats to democracy seriously enough, and my son has asked us what it is about and of course we tell him because I don’t really shield him from anything anymore, which is probably further than Dr. Levine wants me to take things. “What will we do if the Governor gets recalled?” he asks. I don’t remember what I tell him, but it isn’t “we would crawl so far into the depths of our own shame at having thought we would somehow be protected from all of this that we would eventually implode.” I guess there are some things I am still keeping from him.

Then, after all of this, the advice and research, the should I or shouldn’t I’s of parenthood, the other night, while I was reading my daughter a bedtime story, my son walked into her room, which I tell him repeatedly not to do at bedtime, and proclaimed “Mama, I just wiped my butt my whole self!” No one had really asked him to do it, or thrown him into the deep end, or modeled, or taught, or made a plan or set a limit. He just—wanted to—I guess. Our parenting had nothing to do with it. Or maybe, in a sneaky way, everything.

I don’t know if, later, curled up in his bed, under the ratty old blanket his great-grandmother made for his father when his father was born over 40 years ago, he developed a case of punch butt. I suppose if he did, he dealt with it himself. I hope I will not Munchausen my son into fragility, but I also believe there is more to raising children well than what happens within the walls of your home, that the things I do to for the well-being of others will trickle down to his own well-being. I still remain skeptical that we have any idea what kind of childhood will prepare someone for the decades to come, but if hope remains available to me this year, I will try my darndest to hold on to it.

-Where is your uncertainty meter and how do you grapple with raising future generations amidst it? How did you learn to wipe your own ass, or are you still learning???

-Cause I’m clearly on this tip, I just read this Lydia Kiesling’s piece, The Whale in the Room, in the Cut, on talking to her children about climate change, and I think you should too, it’s great. Love her style.

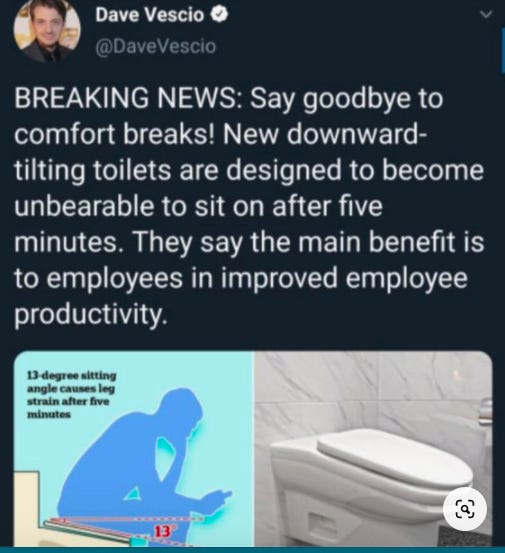

Also, this:

I discovered a late-stage capitalism Pinterest board and now I can’t get anything done…

Thanks for this cathartic article. I grapple with this everyday. How do I raise my kid to be optimistic when I'm so cynical about what's to come? It doesn't feel fair to him. And yet, lying to him about the future doesn't feel honest. I guess this is the price we have to pay for bringing kids into the world right now. On the other hand, there are so many advantages to being alive right now in this time and place (I mean, it couldn't have been fun being a parent when you knew your village could be burned to the ground at any moment by barbaric invaders, right?). I'm just doing the best I can to raise a good, community-focused human. I definitely want him to wipe his own ass (happened naturally...around 8, like your friend!) but also, if he asks for an extra cookie at dessert, I'm mostly like, "eh, why they hell not?"

One thing I've always let guide me in my parenting is, am I being real with my kids, or artificial? I don't know if my approach is best or not, but I do know when I'm exerting extraordinary effort to accommodate them, or when I'm tuning them out to an absurd degree, and I generally try not to do either of those. I will say that I'm often surprised by other people's parenting, in that it seems to both accommodate kids' minor whims more than seems healthy, and also to tune the same kids out with TV more than seems healthy.