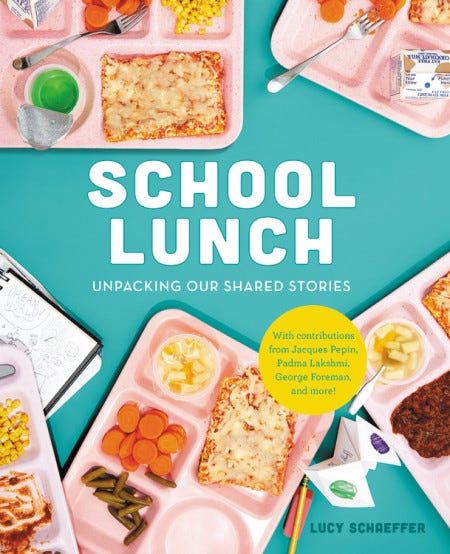

Lucy Shaeffer’s marvelous book, School Lunch: Unpacking Our Shared Stories, was released this month, and even if you only have a permanent pile of your three-year-old’s crap in the middle of your living room in place of a coffee table, you would be wise to find a place for it there. Shaeffer, a photographer, interviews famous-and-not- folks about what they ate for school lunch as a child, and then includes visual recreations of their memories. The book is bright, tender, funny, and, at times, devastating. We learn about moms who made the same sandwich every day for 10 years, foods that were stigmatizing or prideful for kids from different cultures, places where school lunches were works of art (Sweden, naturally, f those guys). One of the most gripping interviews is with George Foreman, the boxer-turned-grille-trepeneur, who is also the father of seven daughters and five sons, all named George. Foreman grew up with so little money that he usually only ate one meal a day. He almost never had a lunch to bring to school, so he used to, pardon my tears on the keyboard, blow into a paper bag and fold it at the top so that it looked like something was inside, and bring that to school. At lunch time, he would secretly flatten it out, and then tell his friends and teachers that he already ate his lunch earlier in the day. He used and reused the same paper bag until it wore out. He was always hungry, and this hunger defined his childhood. He tells Shaeffer, “On the days when I didn't have enough food there was always a reason to start or finish a fight." Foreman fantasizes that free lunch would be available to all children at school, so that the ones who couldn’t afford to bring their own didn’t stand out.

Well, Foreman is getting his wish, in a way. This year, the USDA is reimbursing school districts nationwide for breakfast and lunch for all students. And this summer, the California state congress and Governor Gavin Newsom passed a budget that includes a provision to continue funding free meals for all students, during the school day. No more cumbersome and potentially embarrassing applications for free lunch, no more having to get to school at 7:30 for the free breakfast program if you need it. There are a lot of bad political moves afoot in our country (including the campaign to recall Newsom, who is kind of a skeezeball, sure, but is not an alt-right anti-vaxxer), but the free meals program is an incredible and progressive feat. Maine has also, apparently, changed its policies to provide free food for all students, to augment the already available option of reaching your hand out of the windows of your clapboard schoolhouse by the sea to grab a fistful of blueberries.

These changes are monumental, especially give the fact that one in six U.S. kiddos suffer from food insecurity (and it’s gotten worse over the past year-and-a-half). What’s interesting to me, as a brand new California public schools parent, is how this new program is carried out in different ways in different schools. In our school district, where the schools are even more segregated that the city itself, the number of kids who bring their own lunch in each school varies wildly, and assumptions about who will take advantage of universal free meals follow. For a long time now, free or “reduced” school lunches have already been available to some students all over the country, and the percentage of students who qualify for this program has been used as a proxy for poverty-levels. To be eligible for “free-and-reduced lunch,” you have to live at 130% of the poverty line (reduced is 130%-185%). For a family of 4, like mine, that’s just under $36,000 a year. Some schools in the district, like the one my son just began attending, have a student body that is 76% free-and-reduced lunch eligible. Other schools, like one just a few blocks away, have only 12%. Another, a few blocks in the other direction, has 94% of its student body eligible for free-and-reduced school lunch. Wowzers.

I keep thinking about little George and his brown paper bag filled with air. Would he have been happy at my son’s school, where I have watched them eat their breakfast together, just after they arrive, little clusters of children on the blacktop, with their own brown paper bags filled with bagels, fruit, and at times, something called a “Crunchmania Cinnamon Bun”? How would he fare at the school where only 12% of kids live at or near the federal poverty line, where they wait until recess to serve breakfast, which seems like a long time to be hungry if you were counting on eating at school? What about the schools where you still have to arrive before instruction begins in order to catch breakfast-time?

The civics-minded, city-dwelling liberal in me is delighted in the idea of my child eating the same food as his classmates, two meals a day, no fuss or comparisons. But what a privilege to make that choice, and to be able to send him to school each day with the “back-up sandwich” he requests. And though I would like to tell myself that this eating at school is a 100% egalitarian exercise, I’m sure the differences in the student’s economics flair up. (According to my son, though, at least, everyone drinks the chocolate milk.)

For us, food is never insecure. We waste so much food. Not infrequently, we open up our refrigerator to scrutinize the incredible amounts of food we have, then, dissatisfied, we order out for more food. But not making lunch has a palpable positive effect on my time, the staying power of my marriage, the never-ending battle we are in with the fruit flies who lose their g-damn minds every time we even think about preparing food. Though I understand that some parents feel some kind of way about preservatives and sugar and balanced what-have-yous, I don’t kid myself that what I make for my child is so fabulous to begin with. And, though I respect a parent’s right to want to fill their child’s bodies with things that are not Crunchmania Cinnamon Buns, turning down the food that has been offered to all children and that most of my son’s classmates will be eating feels akin to people turning down his school because of its low test scores and small classrooms and not having an arts-integrated STEM lab or whatever. “That’s okay for those kids, they don’t have a choice, but for my kid it’s got to be this other thing.” I don’t feel great about that.

Growing up, for kids like me whose families had the money to send them to school with their own lunches, school lunch was always coveted. I would have killed for a sloppy joe, or, the mother-of-all-school-lunches: french toast sticks. I lived in a highly socio-economically diverse city where the wealthier kids in public school did everything we could to hide our privilege, and wealth was generally not flaunted. No one I knew had a luxury car. When my friends came over and marveled at the size of my home, I was quick to point out that the ceiling in the bathroom had been missing for years, that 20 people lived in the house, that there was nothing but mustard in the fridge. When I got to college, and met kids my age who had their own new cars or used their parents’ credit cards freely, I was shocked and confused. I thought that was something that only existed on Beverly Hills 90210 (even the kids in Dawson’s Creek live pretty humbly). I don’t tell you this to try and sound cool—in fact, my class-consciousness has often complicated my relationships in ways that I don’t think benefit anyone—only because it is true. I was embarrassed of my natural peanut butter sandwiches on whole wheat bread. I know this is not the same as the shame that results from your lunch being thought of as weird by American standards, or being nothing but an empty paper bag. But it is interesting, how school lunch can mean different things in different communities and micro-communities, and how it can also be a great amplifier of the many disparate lives our children are living.

Could school lunch also be a great equalizer? What would it take for every public school parent in California who had the means just to stop making lunch for their children? Or for all schools to think about what it’s like for their hungry children, even if there are so few of them that perhaps the people in charge can’t quite wrap their heads around hungry children truly living in their midst?

Today’s school lunch, according to the district calendar, and “subject to change based on product availability and nationwide COVID-19 related food shortages,” is chicken gumbo. Apparently it is something called a “California Thursday,” which means the ingredients are grown in-state. I am 100% sure that my son did not eat the gumbo, and that when I pick him up and drill him about lunch today he will give me no information other than that he doesn’t like using the “big kid” bathrooms at lunch time and that he played a game where you shoot imaginary foxes with blasters with some kids named Gordon and Ewow. I’m happy for us, as a society, though, that any and all kids can pop into the cafeteria for a chicken gumbo if they want to. I almost wish I could stop by school for lunch, even if the days of french toast sticks are over.

FYI: Lucy Shaeffer’s School Lunch book can be explored and purchased here.

Also, this:

I am winding down from one of my signature three-day-headaches, and haven’t been in a happy place all week. But, it is garbage day, and after dropping my son off at school this morning, I walked past this lil’ mama pictured below, and grinned so big it hurt my atrophied smile muscles. Why do I love tiny trash bins so much? Is it just their miniature-ness? Is it imagining another, simpler, freer, life where all of my weekly household waste can fit into such a wee receptacle? When the powers that be designed this half-bin option, did they think about how adorable they would look among their looming peers? Whatever it is, these things are the frickin’ best.

What was school lunch like for you? What do you think about all of this?? I love your thoughts.

This is such a gorgeous, thoughtful essay! It is so interesting to me how moms (still mostly moms) of a certain socioeconomic class are driven to burnout by the tasks of upper middle class parenting, but still reject concrete things that would help, like public school lunch. I've seen this play out in social media spaces. No one would ever put it as clearly as you did--"good enough for other kids but not mine"--but that's what it is.

I went to a private high school as a free riding faculty child. So there’s lots to unpack there. BUT, lunch was “included” in tuition and everyone had to eat it. It was much like a college cafeteria that offered many options (salad bar, hot lunch, peanut butter and jelly - does that date me that peanuts used to be allowed in schools?). I loved it because that was one place where there was no comparing.

As a vegetarian family though I have been confused by OUSD’s labeling which often shows the veggie sign next to a dish that literally has chicken in the title. What about students who have legitimate allergies? Yes, we have the privilege to be vegetarian but until schools have inclusive offerings I’m not sure we will get everyone eating school lunch as wonderful as that sounds to this privileged white I-care-about-what-my-kids-eat parent.

I’m looking forward to our follow up conversation where you can gently and eloquently challenge my thinking. 😉