The Boy Was Ours

Love and expectation on the Brandy and Monica tour

I love the music in this piece, so I decided to record a reading, complete with singing. Feel free to listen to this piece instead of reading it, here:

A few Saturdays ago, I joined thousands of Bay Area women-of-a-certain-age at what is now generically called the Oakland Arena (formally the Oracle, one of many relics to the professional sports abandonment of Oakland) for the Boy is Mine Tour. The dress code, the ticket said, was “suited and booted,” and suited and booted we were! There were tuxedo vests and mini-skirts and knee-high stilettos and more than one leather trench coat - their owners giving “retired back-up dancer dressed as Blade.” We were there to see two of the most iconic figures of 90s popular music – Brandy and Monica, once rumoured to be rivals, claiming to be best friends.

We slid into our seats just as Kelly Rowland, of lesser Destiny’s Child fame, came out to warm up the crowd. “We’re in our 30s, 40s, some of us 50s!” She exclaimed. “I’m so proud of us.” There was a collective pride for women of 35 who were raised breathing the air of this music – we were wearing the team uniform, weren’t we? But like Brandy and Monica would later, Rowland hid herself in ankle-length coats, eye-covering extensions, and zoomed-out camera angles, almost like she was embarrassed to see us, like we’d all showed up at the high school reunion and she didn’t want us gossiping about whether or not she’d had work done. It was strange, for a concert so celebratory of adult women, why couldn’t we see them up close?

I had to settle for close ups of the women around me - some younger than I’d expected, some, like me, singing along to every single goddamned word or jumping out of their seats when they heard the first few bars of one of their favorites, some sitting looking contemplative, perhaps wondering how in the hell thirty years had gone by since we’d all first heard these chord progressions.

I grew up a white girl in a diverse city, where what I will broadly and clumsily refer to as Black music was dominant. At summer school, we sang Kirk Franklin gospel numbers. After school, Layla Shlack and I watched hours of BET in her living room, acting out the most romantic scenes from Jason’s Lyric and Higher Learning, where Omar Epps and Tyra Banks find love, only to have it taken away. There’s a lot one could unpack about all that, but needless to say I was a prime consumer of Brandy and Monica - not just the radio stuff but the deep cuts, the early debuts, the soundtrack appearances. I won a CD single of Monica’s Aint Nobody at a roller skating birthday party, and after that I was hooked.

Deep throated like me, Monica felt more mature than Brandy, less curated. On the cover of the single, she sat on a motorcycle with a Kangol-like hat, holding a giant rainbow-swirled lollipop and almost smirking at the camera. This was not Britney Spears in a schoolgirl uniform - it was something, I felt, more real, a self-comfort that was still desirable.

Though they both grew up singing in church, their music was not about God, or life in the struggle, like the rap I also adored. When Monica’s The Boy is Mine album was released in 1998, Monica was 19, and I was a high school sophomore, and at night I would draw myself a bath and indulgently close the door of our only bathroom, don a Biore Pore Strip, and fantasize about Evan Alexander while listening to Angel of Mine. Though I was plenty horny, those visions, like the music that accompanied them, weren’t about sex, they were about love, about being loved. I did this again with Alicia Keys at 18 and Amy Winehouse at 21. Now 42, hearing these songs live for the first time and in many cases, hearing them for the first time in years, brought me back to that deep, incessant yearning, part adolescence, yes, but part something else, something imparted.

As girls of the 90s, love was something we were both highly ambitious about and willing to settle on. We lay in our bubble baths, on our beds, talked on our landlines, scheming about how to conjure it, not so much how to choose love but how to be chosen. I distinctly remember closing my eyes and seeing this 15-year-old boy, with his JNCO jeans and oily t-zone, like one sees an apparition of God, while I wrenched the lines from my teenaged heart. When I first saw you I already knew/There was something inside of you/Something I thought that I would never find,/Angel of mine. Love was not content reserved solely for R & B – it was on VHI and every white kids-cast teen movie. To be wanted - serenaded, like Julia Stiles by your own Heath Ledger - was to be exalted.

Brandy too, you must recall, portrayed our culture’s most famous princess. On the bridge of Sitting Up In My Room, her song from Waiting to Exhale, the film that attempted to say, you don’t need a man to define you, but also, it would be nice, she sings I pray that you’ll invest in my happiness. I can feel the sharp pain of those prayers, the ache for that investment. Getting to the other side of being picked, of being loved, was both unfathomably glorious and explicitly underwhelming. On Aint Nobody, Monica’s dream boy is adulated for these unexciting qualities: Never front in front of your friends/Take me riding in your Benz. We had to keep our aspirations high, it seemed, but our standards perilously low.

At the Arena, I looked around me as I belted this line – on one side my girlfriend smiled at me, on the other, the surprisingly young woman, clad in a silver and gold crop top that both nodded to the dress code but retained some independence, bopped along. Down one row, a woman in a collared shirt and hoops rivaled my enthusiasm and lyric knowledge, and a few seats next to her, a man I began to refer to as “my guy” danced with abandon to every upbeat track and crooned with his hand on his heart to the slow jams. Had these folks dreamed, like I had, of the man who would complete them? Had they fallen in love with the first guy who didn’t ice them out when his friends were around? What happened next?

After the Boy is Mine concert, I could barely croak out a goodnight to my friends. They had played all the hits — For You I Will, Sitting Up In My Room, Baby Baby Baby, Before You Walk Out My Life. Somehow, speaking so many words of love, like incantations, I felt my husband’s presence there — a testament that even after all of that unrequited teenaged romance, I’d made good on finding my prince. I bowed out of a second location and took the train home – it was nearing midnight and the battle my body was waging with the magic of the night was about to turn ugly. I sat amongst the other tired millennials, my husband’s tie around my neck, my feet pulsing from hours of being “booted.”

In my ear was a very different sound – Lily Allen’s concept album West End Girl – which I had been playing on repeat for weeks. In it, Allen, who had a career as a young It Girl a decade after Brandy and Monica, tells the “auto-fictional’ story of a woman reluctantly agreeing to an open relationship that is simply a gateway to her husband’s cheating and sex addiction. In chronological sequence, she discovers this fact, expresses her heartbreak, says good riddance, balks at dating as a mom of teenagers, and mourns her relationship once again.

Unlike Brandy and Monica, who were not necessarily styled as angelic but peddled their share of innocence (“I don’t get down on the first night!”), Allen’s public persona has always been one of uncontainability and rebellion. She sang about smoking weed and everyone going and fucking themselves, assaulted a paparazzo, cheated on her own first husband with an incredible line-up of trysts — bad boy musician Liam Gallagher and several female sex workers. If the women of the 90s sang about love, the women of the aughts shifted their focus to empowerment, to self-worth.

But despite her independent veneer, Allen – or the version of her created for this album, which most people believe is just her – was willing to tie herself into knots to please her husband. On the title track, we hear Allen’s side of a Facetime call with him, in which she reluctantly agrees to release him to have sex with other women saying “I just want you to be happy.” As the relationship deteriorates, Allen sings to this pseudo-real husband, “you give me just enough hope to hold on to, don’t you?” Hope for what, I wonder?

Brandy and Monica are both 46, Allen, 40. I could be their middle sister, and thinking back to our childhood, I can’t help but wonder if that hope wasn’t for any one specific thing or person, but for the preservation of a fairy tale, the only acceptable conclusion to girlhood.

I cannot speak for the woman with the hoops, but the girls of the 90s, all grown up, seem to be having a collective reckoning. Even the men we thought were evolved have turned out to be disappointments, to wrap us up in their narratives about masculinity or to effectively leave us to manage family life. In the domestic thriller All Her Fault, released this month on Peacock and starring Sarah Snook and Dakota Fanning, Fanning’s character tells her husband, who has been lying about work responsibilities so he can watch Tiktok in his parked car while she cancels her own meetings to pick up their six-year-old son, that she wants a divorce. When her husband worries that she will keep their son from him, she explains that she would never do that, But, she continues, “When he gets older, he’ll look back on this and he’ll understand what happened, and he won’t treat a woman the way you treated me.” Men like this, “my guy” at the concert excluded, didn’t learn from an early age to do anything for love. They were tasked with finding someone to ride them (My saddle’s waiting, come on jump on it), with giving women advice they didn’t ask for (come on try a little, nothing is forever), they were having an indecipherable blast with two turntables and a microphone.

Maybe it isn’t just that I wish we’d been given other stories, that organizing our lives around a monogamous partnership that would solve all of our problems and make us worthy of existence was probably not a good thing. Maybe I also wish some of that desire – not the parts where you lose yourself but the parts where you care about earning the love of those around you – had been handed down to the Evan Alexanders of my generation, too. When I watch my daughter listening to the ballads of finding a good man, which time has not completely diluted, I don’t just want something more for her – I want my son to also hear about relationships as aspirational, to imagine the good parts of wanting to be better for someone else, whatever dreamy expansiveness brings you to the place where we pick up our child from school so our partner can further her career.

Monica has been married three times, the third marriage was earlier this year. Brandy was engaged twice, and at the age of 22 faked a marriage to the father of her child to avoid public scrutiny. I wonder, all the way back then, if she’d longed for him to ask to make it real, or if she’d known better. She never did marry. For the hour-and-a-half that they performed — in heels and on fainting couches, casually resting on stools or sitting in front of a piano — I couldn’t really see her face. But she sounded happy, and I’d like to believe she is. Never say never.

Also, this:

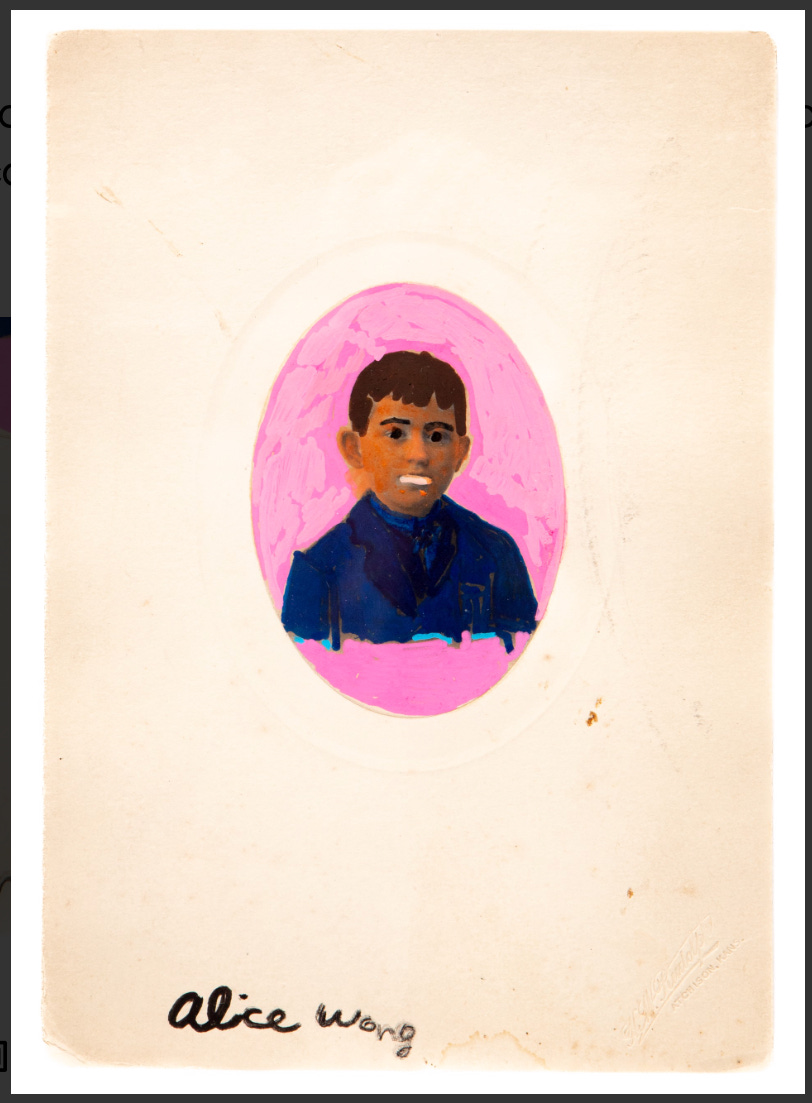

Tons of dope holidays gifts at the hope of disabled-artist collective Creativity Explored (SF) and Creative Growth (Oakland) - where 50% of profits go to artists and 50% go to sustain the work of these incredible organizations. Playing cards and original art by the late, GREAT disabled-activist and artist Alice Wong:

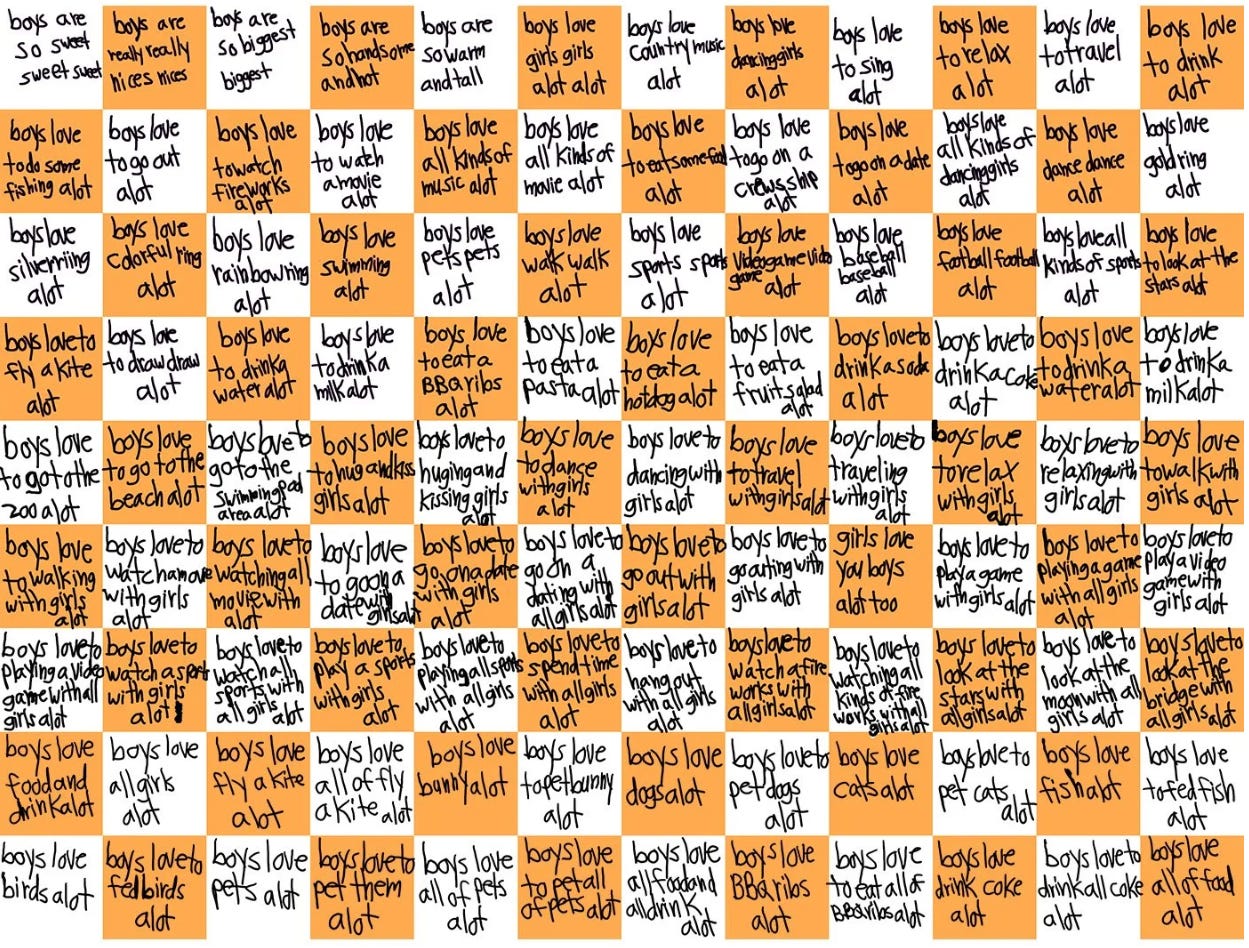

And $20 wall prints like “Boys Love” from the artist Zachary Adams, below.

Like the sound of my voice? You won’t believe how much of it is on my two very wonderful podcasts, The Mother Of It All with Miranda Rake and This Week in Breeders with Garrett Bucks. Our latest episodes are all holidays, all parenthood, gender, and division-of-labor chat.