Transitional Objects

What do we need to come out of this moment intact?

I took my son on a trip to Portland last weekend, and it was pretty darn sweet. There were Salt & Straw ice cream cones, unexpected cherry trees, visits to the storied Klickitat street, where we searched for Henry Huggins’ house based on a five-year-old’s description, and a beautiful beach that turned out to also be nude (“Mama, why were there so many penises but not so many vaginas” “Well kid….”). But like all adventures, there were disappointments and setbacks: the dispiriting return of the packed flight with that inevitable-yet-puzzling lack of space in the overhead bins, the oppressive heat that threatened my son’s delicate Bay Area disposition, and, I am sorry to report, with the exasperation and disgrace of all parents who have tried and failed to contain something they cannot, the acquisition of not one but two new stuffed animals.

Like all children forever ever, at least since the invention of soft materials, my son has way, waaaaay too many stuffed animals, or as he calls them, loveys. It all began, nigh on five years ago, with a desire to get him out of the swaddle and a harmless-enough suggestion from his pediatrician about purchasing something to replace it. His first relationship was an exclusive one, for almost three years, with a muslin cloth attached to the head of an elephant, which we named Stampy, without his input. But the sweet life with Stampy ended abruptly when we accidentally left him at a Porto Airbnb. We tried to comfort Max with Stampy’s head, which had long since relieved itself of his body and was waiting for us at home, and I suggested that I could sew it on to another cloth to make a kind of zombie Stampy. But that was not compelling, or perhaps too morbid, and thus began a string of affairs, passionate but short-lived, with an eclectic series of plush partners. There was the half-cactus-half-sloth, “Z2,” the creation of some mad scientist, which we discovered in a bookshop in Tucson. Then Z2 was replaced by Snakey, a, you-guessed it, red snake purchased at the Oakland Zoo in a shameful moment of “whatever, it’s hot, I’ll do anything to get you to happily walk back to the car.” Max took to strapping Snakey to a plastic baby seat on the back of his bike, so that when he biked around the neighborhood he looked like a young father taking his baby snake to pick up a few things at Whole Foods. And before them there were an axolotyl, pink and, we were reminded, critically endangered, that fit neatly under his pillow, and a series of cats of all sizes and colors, which were unfortunately difficult to distinguish from the many similar cat loveys owned by his sister. At this point, a good ten percent of our two-bedroom apartment is devoted to loveys, with no end in sight. I consider my son to be the Leonardo Dicaprio of loveys — he seems to be having a great time with whoever he’s spending time with at the moment, but it is very difficult to keep track of his affairs of the heart.

Imagine my dismay when, just minutes off of the plane in Portland, high on the possibilities awakened by air travel, he fell absolutely, head-over-heels-in-love with a tiger that had slap bracelets for arms, hanging from a display at a magazine stand. Two days later, not to be satisfied, he chose as his one souvenir from the Portland Science Museum gift shop a creature that I can only describe to you as a “pig fish,” but which was lazily thrown in with merch from the dinosaur exhibit. “Diney,” who, I’m telling you people, is one of the most confusing things I have ever laid eyes on, is now a fixture in our family: he travels to school with Max, snuggles him at night, causes great distress when he cannot be found (though it is hard to lose him, he is a very bright and off-putting combination of orange and red that I can assure you is not found in nature).

Donald Winnicott, the same psychologist who came up with one of my most favorite terms “the good-enough” parent (well, actually, he said “mother” — sigh), also coined the phrase “transitional object” in 1953. Winnicott defined transitional objects as anything a child forms an intense, persistent, attachment to, and believed not only that these attachments were universal, a sign of “good enough” parenting (ok, mothering, ugh), and would at some point be able to comfort a child even more than it’s parent, but that these objects were also essential to a child’s ego development. It was through the transitional object that a child developed a sense of self, or, as one psychologist with the delightful name Carole J. Litt puts it “distinct from all other parts of the external environment.”

In my own childhood, I had many such objects. The most memorable, a stuffed bear named Randy, was given to me at the age of four for “stuffed animal night” during Hannukah (my parents gave a theme to each of the eight nights, some more exiting than others), and I still sleep with him every single night. His fur is quite matted and his nose was chewed off my a black lab named Bruno but I think he is perfect and have no intention of ever giving him up. My brother had a blanket named “Nigh Nigh” who we joked would probably accompany him down the aisle. Nigh Nigh used to stow away inside a pillow case when my brother went on a sleep over. Like many parents, my mother had to carefully sneak Nigh Nigh out from under her child’s sleeping body, wash him, and return him before morning.

On the day my parents told me they were separating, which was not a surprise but was still painful, there was a big fair in the center of my town. It is my memory, though it might not be true, that my babysitter Chris took me to the fair, where I lusted after a pink plastic treasure chest, complete with tiny key, in the vaguely-fair-related offerings of some vendor. After we went home and had our “family meeting,” I convinced Chris to return to the fair and buy me that treasure chest, which he did because he hated saying no to children, even those whose parents had not just this minute explained to them that they didn’t love each other anymore.

Was that pink plastic treasure chest my transitional object? I don’t have any memories of it after the day it was purchased. Did I take Randy back and forth from what was now my father’s house to my mother’s new apartment? When I think about it, it’s clear that my siblings were my transitional objects back then. The older ones eventually set their own adolescent schedules, but I distinctly remember, after my mother moved out, the anxiety of leaving my little brother at home, like going out of the house without your wallet. And, though I have lived 3,000 miles away from him for 20 years, I still, from time to time, have the urge to tell him that I will be right back.

These days, I find myself searching around for something to aid my transition from “person in a global pandemic” to “person acknowledging that there is still a global pandemic but her everyday life is no longer a crisis.” I think of what it felt like a year ago, when I was existing inside some kind of warped womb, and ache for it. There is something that feels unsafe to me about this new world, and some of that danger is good, is a sign of growth and reckoning with the truth. But I want a new sense of self, a clear distinction, and I’m not sure where to locate it.

There is a part of labor, called “transition” when your cervix stretches to its absolute limit and you get ready to push. This is the point where women often puke, shake uncontrollably, or in my case, beg to be given the drug that feels like “too many margaritas.” Though other people in our eye-roll-inducing but helpful hypnobirthing class loved learning about the mechanical details of labor, I wanted no part in it. Knowing that I was “in transition” did not seem like it would be helpful information. I trusted the process, held tight to my mantra that my “body knows what to do, my baby knows what to do” even if they had both left me completely in the dark. But to others, this knowledge was everything.

This transition, it should be noted, has a clear endpoint — though there are harder and easier ways to arrive there. What would it mean to envision an endpoint for this moment? And would it somehow degrade the mucking through that needs, I feel, to be mucked? I have felt called, after almost forty years without one, to get a tattoo. I cannot tell you what it will be, because of the universal law that as soon as you describe a tattoo to someone, it no longer sounds cool, but I am so in need of a reminder of where I came from and where I want to be going that I am insisting that that reminder be stamped on my flesh.

Sometimes a transitional object serves as a distraction — something you can grip, white knuckled, while the pain of limbo washes over you and passes by. Sometimes it is a reminder — you are still you, even though you are now also a Kindergartener or a child with two homes or a worker putting on pants and driving to an office. Some container you were relying on may have flown open, you may feel like you are being spilled out into this new experience, but you are still an intact being.

There is a notorious story in my family, of my step-brother, who, before getting married, had a number of serious romances without many transitions. He is explaining his approach to a third or fourth date — when you know each other well enough, and things are going smoothly enough, that you invite her over for dinner. In this scenario, he always wanted to impress her with his cooking, make her feel treated and cared for. But, he also pointed out, it was important not to let her just sit there, receiving. “You’ve got to give her a task,” he explained, like chopping herbs or peeling vegetables, even if it was superfluous to the meal. This was not a condescension—but a sign of respect and romance. Too much dead time, at this ambiguous moment in a relationship, was threatening. People need purpose, regardless of whether their work is essential.

I wonder, then, if we also need transitional activities. For the first several weeks of preschool, every single day, my son would ask his teacher Gladys if she would “call mama and dada” while he napped. Gladys would assure him, when he woke, that she had, even though we never once received such a phone call. My son never asked us how these calls had gone, only reported that Gladys said she had called, and seemed satisfied with that. He did not need to speak to us, he did not need us to come get him, and we were all pretty confident that he knew, somehow, that these calls never took place. But he needed the ritual of it, the control, the action. When he was ready, he stopped asking Gladys to call us. The transition was over.

A transitional activity can be a diversion from our own messy feelings about the transition, or it can be a way to move through it with some measure of groundedness and grace. At the beginning of the pandemic, as we transitioned into something we couldn’t even imagine yet, many of us took to crafting, bread-making, vegetable-growing. This was a way to pass the time, sure, and something to consume our attention and give us a small feeling of tangible accomplishment in a shapeless shit storm.

But for some it was also a meditation on what is vital and what isn’t. To be alive and well, all I need is to put my hands in the dirt, to feed my family, to access that most generative of feelings: pride. There were other activities for other moments—in my neighborhood picking the seasonal fruit growing in our gardens, on neighboring trees, took on way more significance than it warranted. Our carefully planned and then hastily cancelled winter holiday plans allowed many of us to experience a sped-up emotional arc that was difficult but necessary for us to process the feelings of the moment. Memes about Bernie’s mittens carried us through a tense changing of the presidential guard. And this Spring it almost felt, if you’ll indulge me, that transitioning was our transitional activity. “Holy moly, we’re opening up. I took my mask off out an outdoor restaurant. I went inside someone’s house and sat on their actual couch!” But what are we doing now, when many people have decided the transition has ended but others, myself included, will not be hurried along?

Winnicott felt that transitional objects were always temporary. Get through this moment, get a little further from home, and be done with it. He wrote, of the transitional object; “Its fate is to be gradually allowed to be decathected (to have one’s attachment to it withdrawn—I had to look this up), to be relegated to limbo. It is not internalized, forgotten, or mourned.” The bread making, for example, served its purpose for many of us, and went as quickly as it came. Thank you for your service.

But I still feel in my body that I am too far from the home I was born in, and I still can’t sleep without clutching a ratty, middle-aged, child’s toy, and I don’t really care whether this transition has an end anymore, I just want to distinguish myself from all of the mess while I stumble through it.

What’s your transitional object? Activity? How do you know your self made it through to the other side, and it’s the self you wanted to take with you? Does it help you to call this a transition? Or, can we convince each other to trust the process?

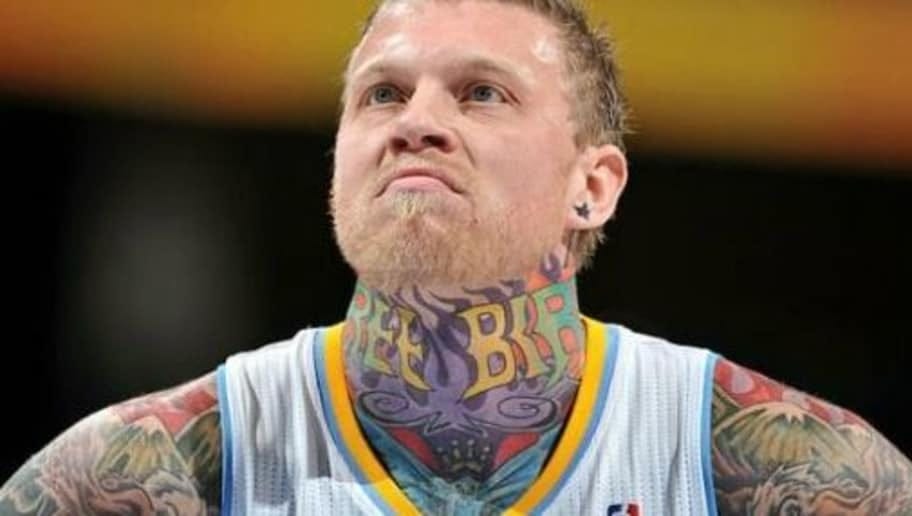

Basketball reference as transitional activity? I now have SO MANY ROCKS. My desk looks like an Andy Goldsworthy commission. When I was a kid I wore this one pair of reversible "jams," as in "Jimmy Jams," that they were literal shreds by the time I gave them up. And even then they became pinned to my wall. I take issue with the lack of mourning, because I think it depends on the degree to which you personify objects, something that autists (and I) tend to do prodigiously.

This made me cry!!!