How Can I Stop Making Empty Threats?

Also if you don't open this email I will throw your computer out the friggin' window, I swear to god.

A few months ago, when I solicited questions from readers about kids and parenting, one of you asked: “How can I stop making empty, inorganic threats? (I think this might be one of the worst parts of my parenting default.)”

This is a great question, and though I of course had grand visions of answering one of these reader questions weekly or the like, and then maybe getting noticed by Reese Witherspoon or Oprah, getting a book deal that somehow didn’t feel pressuring and allowed me to write a book where I basically didn’t say anything, and getting rich enough to fly in the part of the plane where you can take a shower, none of that happened. But I’m here, having mulled over this one for quite some time, ready to give it my all.

A word about parenting advice: it’s annoying, and not always useful. I don’t know shit about you, your family, your culture, the gifts you bring to the impossible task of raising children, or the baggage you’re carrying from your own imperfect upbringing (we all had one). Also, as I found in being first a professional-parenting-advice-giver and then a parent, parenting your own children is way harder than telling people how to parent theirs. So, I always try to include the messy truth about my own attempts at things at home in my suggestions to other parents, but also, please take the following as one way of seeing things among multiple possibly equally good ways, and as something to be curious about, rather than something to immediately adopt or feel shitty for not adopting.

Ok, we shall proceed.

There is a family story, deep in the Wheeler cannon, from when my dad was a little boy, which I remember like this: It’s Texas in the 50s. My grandmother is driving her young son, my dad (who in my mind is just my dad’s adult head attached to a tiny body, like the drawings in Lil’ Archie) along a country highway (obviously he is in the front seat, and neither is restrained in any way) in what I always imagined to be a powder blue T-bird, but it almost certainly was not. The mother, my grandmother, in classic 50s fashion, is smoking a cigarette while she drives, tapping her ashes into the car ashtray that sits in the console between them. The son is trying to tell his mother something important—perhaps about a recent academic triumph in his one-room schoolhouse, or setting a personal record in hula-hooping or something, but she is not listening. Maybe his mother is fantasizing about a life where she has something to do other than smoke and care for children. Maybe she is planning dinner. Maybe she is counting telephone polls or tumbleweeds or something. Every time he offers another tidbit, her response is only “that’s nice dear.”

“We chased that local tabby cat into a tree!” “That’s nice dear.” “And old Mister Shoemacher told us we were thick as fleas on a farm dog!” “That’s nice dear.” “And then we got a RC Cola from the icebox.” “That’s nice dear.” Finally, feeling that he has no other options, the son gives an ultimatum: “If you say ‘that’s nice dear’ one more time,” he tells his mother, “I’m going to throw this ashtray out the window!” The mother replies, “that’s nice dear.”

To the astonishment of both, my lil’ dad makes good on his promise. He chucks the ashtray, butts and all, out of the car window and on to the side of the highway, never to be recovered.

We all lose our shit with our family sometimes. Parents are distracted, partners are unreliable, children don’t write nearly enough thank you notes and say hurtful things like “I don’t like it when you do that accent.” Threats are an inevitability.

And, as a parent, making an empty, irrational threat because you are losing your g-damn mind is not the end of the world. Parenting is insane, and we all do stupid, ineffective shit sometimes in the wake of it. Despite what some parenting experts want you to think, (because saying “we don’t really know much about parenting other than that we shouldn’t abuse and neglect children” isn’t very catchy), there’s no research that says that children of parents who make an empty threat a day fare better than those who only make one a year. And if that research did exist, you could bet your bonnet that it would be done on a small group of middle-class, college-town-adjacent White families, with no regard for cultural differences or the incredibly complex context that each and every parenting decision exists within.

Your frustration communicates something potentially effective to your child; that you are not feeling like they are keeping up their end of the relationship bargain. But the annoying thing about kids, other than how bad they are at cleaning up after themselves and putting their shoes on, is that they aren’t adults. Guessing at your motivations and taking care of you is not a reasonable task for them to do all of the time, and in fact, in extreme cases, that work can be quite traumatizing for them (I am not saying you are traumatizing your child, and in fact I take issue with a lot of parenting doctrines that equate trauma with like, maybe not getting the most relational, healthy parent every second of the day).

The main thing here is that, making an empty threat doesn’t usually get you what you need, and in fact you are more likely to get what you need if you do the guess work for your children, and very plainly tell them what your limits are and what will and wont happen when those limits are breached. But often we don’t even know those things ourselves. How much is too much to take from our kids? At what age is it unreasonable for them to still xyz??? When does the pervasive, unavoidable vibe of being taken for granted, which naturally permeates the parenting experience from day one, become egregious?

Also, as our reader hints at, unless you are as ballsy as my six-year-old dad, making an empty threat usually feels pretty dumb, and you never go through with it because it’s ridiculous, and likely isn’t something you really want to do anyway. Hearing yourself say the words “Well maybe you just can’t handle having shoes!” is not especially fun, not nearly as fun as it would be to gather up all of the shoes that they take forever to locate and put on, despite doing it many times a day, tie them to a brick, and make your child watch as you throw them into the nearest body of water. But then you’d have to buy new shoes, because you are a grown-up and a provider, not a clever six-year-old with an adult-sized head.

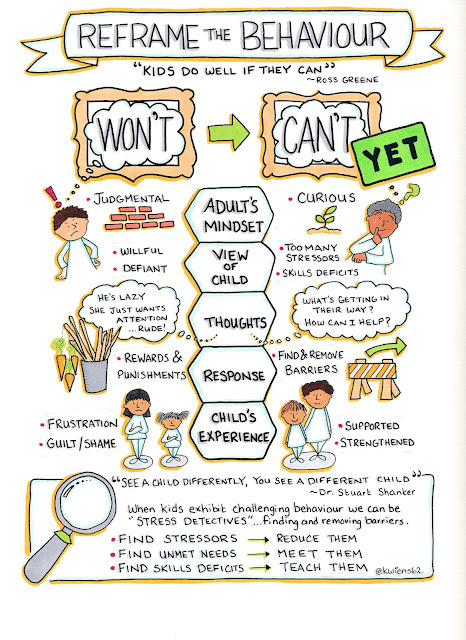

There is this lovely phrase, given to us by psychologist Ross Greene, author of The Explosive Child and Raising Human Beings and owner of a delightfully subdued Boston-area accent, which I return to often both personally and professionally: “Kids do well if they can” (as opposed to “Kids do well if they want to.”)

If kids could do better, they would. Misbehaving, disappointing people, those things suck, and even kids try to avoid them. When we do well, it’s because we can, because doing well is always a nicer experience than not doing well. When we don’t do well, it’s usually because some factor or combination of factors, maybe invisible to others, made it too hard for us to do well. Kids are inconsistent, they often put their shoes on fine one day and not the next. The idea here is not that they can’t ever put their shoes on, because we know they can, and even exasperatingly tell them “you KNOW how to do this!!!” but that in this particular context, with this set of conditions, they actually cannot.

So, then, the first question to ask yourself, reader, when you find yourself becoming a maker-of-empty-threats, which often happens in the same situations over and over again, is, what conditions could be altered and what skills could be taught to allow them to do better? The first part of this acknowledges that, even though we cant control the little buggers, we are the parents, we do make the rules, we do buy the shoes with the hard-to-tie laces and decide where things go in the house and make the schedule and all that good stuff. Which of those things are helping your child do the thing you want them to do, and which are holding them back? The last part of this is about our unique child. Some kids can totally put their shit away when properly motivated, others just literally have no idea where anything goes, or look at a messy room and in their minds see something totally fine. So for the first part their will be environmental changes necessary. For the latter, explicit teaching and modeling (here is how you put your shoes on, step by step), practice (now you do it!), and patience (maybe in a few months this will be easier).

The second question is, “have I, the parent, in a calm moment where there is not something else going on and maybe where hot chocolate with whipped cream AND sprinkles is being consumed, plainly (and not excessively or obnoxiously or defensively) expressed my concerns to my kid, asked them with genuine curiosity about their experience of the situation, and invited them to problem-solve with me?” Ross Greene calls this the “collaborative problem-solving conversation.” Other parenting philosophies, like Positive Discipline, get at this through “family meetings.” The Greene way, which he also refers to as “Plan B” (in contrast to Plan A, which is imposing your adult will) goes like this: You start by neutrally stating what you’ve noticed about a difficult situation, invite the child to tell you about their experience of it, and then AND ONLY THEN, introduce your own frustrations. If this sounds weird to you, you get used to it. In the getting shoes on case, it might go something like this:

“I hope you’re enjoying your cocoa and its many toppings. I’ve noticed that you are taking a long time to put on your shoes and get ready for school these days, what’s up?”

Here is where your kid tells you all sorts of things you have and haven’t thought of, like that they hate these shoes, or they just want to play, or they are actually feelings anxious about getting to school, or they don’t like the color blue anymore, or they have too many things to remember in the morning. Or they tell you nothing at all, and you gently question, and maybe accept they aren’t gonna give you an epiphany this time, but you at least gave them the opportunity (Ross Greene wouldn’t want you to give up, but sometimes I do).

“Ok, so let me get this right, you __________ ? And that’s why you’re having trouble getting ready? Cool cool. So the thing is, that I get frustrated asking you many times to do it, and when we get to school late, I’m late for work.”

“What do you think we could do that would help both of us get what we need?”

Sometimes the ideas are revolutionary, sometimes they are just a much more relational, empathic way (on both sides) of solving something that making the same empty threat over and over, and the connection that these conversations make does, even slightly, ease the tension in the problem situation. My six-year-old son has told us that he really hates being nagged, so we’ve agreed that if he does what we’re asking the first time, we won’t repeat it (this doesn’t always work, but it helps me notice his point that I do say things a million times and it’s annoying). We also put up a little drawing with the stuff he needs to be ready on the back door, so we can point to that instead of nagging. He explained that he doesn’t like getting ready first and then playing, he wants to enjoy himself and race at the last minute. As long as that works okay, it’s fine with us. We use a Time Timer, something I’d recommend for all households with children, that goes off five-minutes before we have to go.

It is not only imperfect, but riddled with ups and downs, immature moments, and stuck places. We all slack, and conditions change. One day my son ripped the chart off of the wall and threw it at me. But we try as best we can to remember to check in again, adjust things, continue to be empathic to one another, and as parents we ask ourselves what really matters to us (getting to school on time most days) and what doesn’t (wearing real clothes versus pajamas). Sometimes we spend days and even weeks in empty threat territory without recalling any of these helpful solutions. Sometimes we ask our three-year-old to chime in, and she says she just wants to be a cat in the morning, and we honor that, and the cat (her name is Cookie) is somehow way easier to get ready than her human counterpart.

There is one more option when finding yourself in empty threat mode. It’s what Greene calls “Plan C” or temporarily dropping the expectation. It doesn’t mean you “give in.” It means you say very explicitly that because things are not working, you will change your plan, and together you will make a better one as soon as you have time and space and calm. “I don’t like putting your shoes on for you, and that’s not what we agreed, but we are late so I am going to help you today. After school we can work together to make a plan that works better for us for tomorrow.”

Like everything in the whole wide world except D’Angelo’s abs in the year 1999, this is all imperfect. We don’t do it because it is perfect, or it promises us a child free of pain or a home free of conflict. Those things don’t exist. We do it because it makes us feel a little more grounded, and recognizes our own experience and our child’s experience as valid and useful, rather than seeing ourselves as put-upon and our children as nemeses whose only goal in life is to make ours difficult.

It’s funny, when I went to write the story about the ash tray, I realized that I have no idea what happened after my dad made good on his threat; whether he was punished or made to put all of the dimes he’d earned shining loafers or whatever towards a replacement. That part of the story wasn’t important to us. The meat is the small, silly victory, the brazen follow-through, the sun glinting off metal as the ash tray and everything it represented met its rightful end. The story doesn’t work if the grown-up wins, if it ends with a spanking or a grounding or a repossession of a beloved hula-hoop. Because us making good on our empty threats isn’t funny, it’s at best, bizarre. We tell the ash tray story cause it’s cute that a kid did it. But if an adult did it, they wouldn’t talk about it, except maybe in therapy.

But we all get to empathize with the desperation, and fantasize about having the courage to go just a little bit crazy in the face of familial injustice. You can throw your kids toys in the trash, if you really want to. But I have the feeling you’d rather not, if for no other reason than that it doesn’t actually teach your kid what you want it to.

Thank you reader. Make your empty threats. Forgive yourself and your kids. Talk about it in therapy (I know I do). And if you’re interested, learn more about Ross Greene’s ways of working shit out with kids from my much more coherent colleague Liz Angoff. And remember the true lesson here; don’t smoke with your kids in the car. Do it when you are alone and parked in the driveway, late at night, when you can listen to your jams and have nobody bother you. That’s nice, dear.

Also, this:

It’s been a fuck of a few days. What the fuck. Please read some brief and helpful thoughts on the situation in the Ukraine from my pal Garrett Bucks. I’ve been looking out my window at this beautiful mural by Bay Area artist Marcos LaFarga today and, I don’t know, trying to think good things about the human race. XOXO.

You've done it again, Sarah Wheeler. (i've read Ross Greene and I really like the way you boiled it down). I basically need the reminder (maybe everyday) that kids (and adults, really) often do the best they can most of the time. In major gratitude! MERCI!

This is a masterpiece. Somehow you put a cherry on top, without pretending that the sundae itself is perfect or neat.