A few weeks ago, before the school year ended and we high-tailed it to the east coast for a month of what I call “real summer” (no fog, warm nights, frozen treats abounding), I discovered a pair of running shoes on the street.

Where I live, it can be hard to tell the difference between something a neighbor has left out in order for it to find a new home, and the abandoned possessions of someone unhoused. Often, when shoes or coats have been put out on the curb, we make sure to leave them there — these are hot ticket items for the many in our community who don’t have consistent housing.

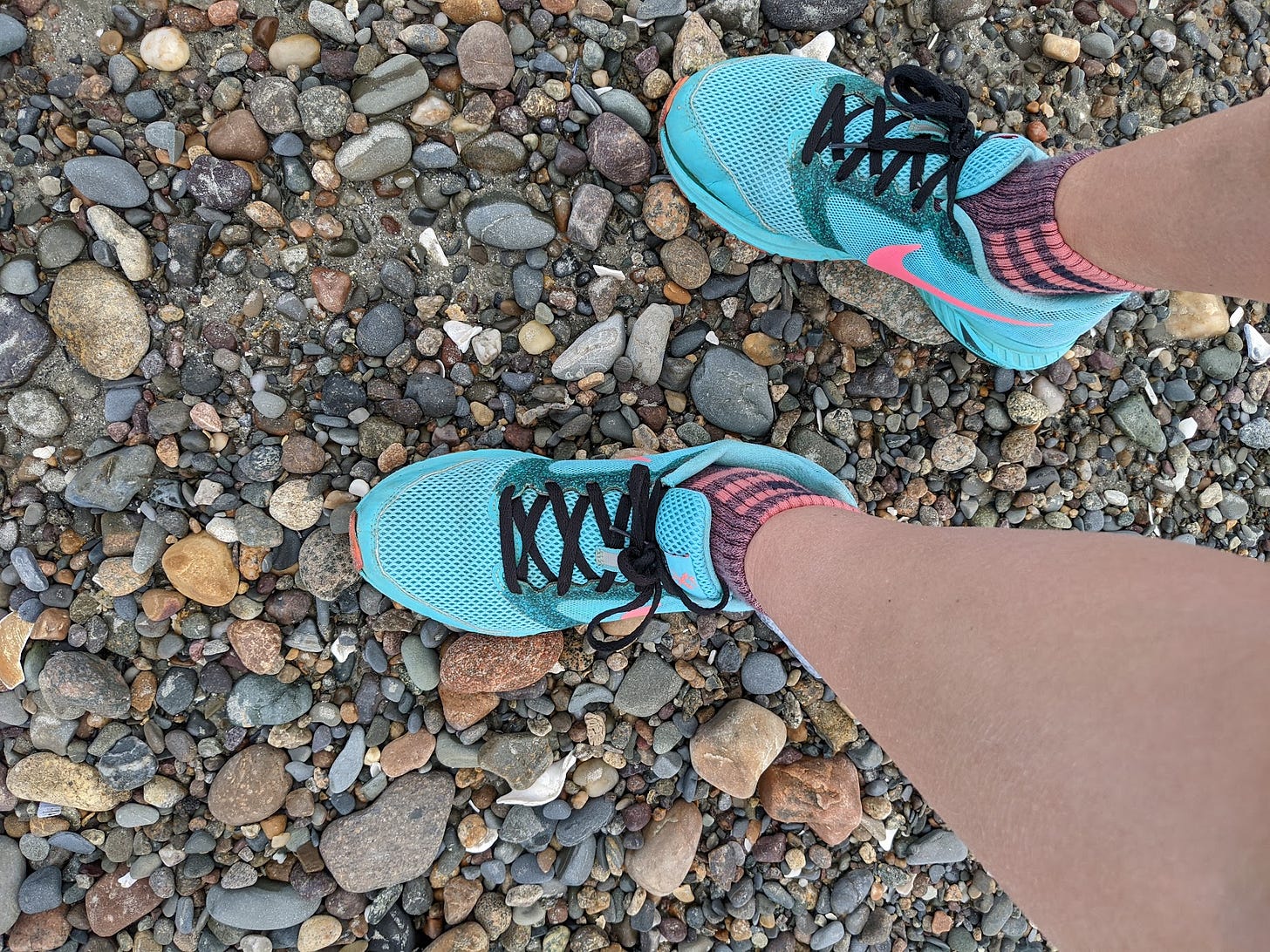

These shoes were positioned to attract positive attention, as if the sidewalk were a storefront. They were my absolute favorite color and my exact size. They looked clean, like someone had just put them through the wash. I don’t know what mixture of pragmatism and impulsivity caused me to bring them to my nose and inhale their scent, but, thankfully, they smelled very, very good. I hesitated for a moment, imagining someone whose soles had worn down stumbling upon them with relief, or, just as likely, inclimate weather and city-street-shenanigans destroying their perfect state, so that I would have to walk past the right shoe a week from now, filled with what I hoped was animal feces, blocks away from it’s origin and think, “it could have been different.” I took the shoes home, giddy with my own luck. But there was one downside: now I would have to use them.

I am an indoor kid. I spent my childhood writing poetry and performing in socialist-leaning children’s theater productions. No one taught me how to catch or throw. If I ever joined a sports team, it was only to sit on the sidelines, adjacent to my friends, trying to avoid eye contact with anyone who had the authority to put me in. When I was a bit older, I did sometimes play on my dad's Nautilus reformer in the basement, but this was just as fantastical as playing princess: I was more likely to marry the Prince of Monaco than to jog a mile on a treadmill. I had no physical confidence, no hand-eye coordination, seemingly no connection at all between my brain and body, beyond how much imbibing sugar made me happy.

When I did finally start exercising for real, in college and graduate school, a physical therapist who inspected my tweaky legs told me that there was nothing exactly wrong, it just seemed like my body was protesting the whole thing. As an adult, I've had periods of rigorous and perhaps addictive physical activity, such as during my paleo diet / 6:00 a.m. boot camp phase, and others which have been, let’s say, softer. Now, I barely sweat beyond the daily grind of wrestling my children and the occasional early morning hike with a friend, which works for me because it is too early to come up with excuses not to go, and because talking the whole time keeps me from noticing that I am, in fact, exercising.

Armed with my new castaway Nikes, I vowed that during this vacation month, I would set a very reasonable exercise goal and see what happened. In normal life, it always makes me have a better day when I do something as small as walk my son to school. I get a little crazy on vacation, without my beloved busy city and my self-heating smart mug. I thought of the parents of the more active ADHD students I’d had over the years, who used to run their kids a mile on the track at 7am, or make them bike to school, and swore by the regulatory effects. I needed to move.

But I am not, by nature, a disciplined person. I have to squint at goals, because if I see them coming, I will turn around and run the other way (okay more like power walk, running still hurts my legs). My brother-in-law, who writes and teaches about addiction, once told me that people like me, people who are high-functioning, don't need discipline. We can get by without waking up at 5:00 to do an hour long yoga practice every morning. I was flattered, in a way, but, as I've turned it over and over in my mind over the years, I wonder if I don’t go too far in the no discipline direction. I cannot tell you the time I waste as a result of refusing/forgetting to look at my to-do list each morning. Even scheduling “check to do list for the day” as a daily alert does nothing.

I settled, without giving it so much thought that I would give the whole thing up, on a goal of two miles of movement a day, whatever form that took. Surely, quietly vowing to move two miles in a forward direction each day, when nothing else is going on and other people are entertaining my children was not discipline—it was just the vocalizing of a small, reasonable desire.

My neighbor on the plane back east, who was returning for his 30th Harvard reunion, upon learning I was some kind of psychologist, told me how much taking the Myers-Briggs personality test changed his life. He is a scientist, and never really thought about his personality and what it meant about his work life, but once he found out that he was an extrovert, he realized he should quit his job at IBM and become an entrepreneur. He has been very happy ever since. We talked for another hour or so, about his unmotivated teenagers, and whether ADHD was a disease (him) or an identity (me). He was that rare mix of very opinionated and smart and also very curious.

Because I liked my neighbor, and was also a little bored, and because JetBlue now has free Internet on their flights, which I am ambivalent about, I looked up his favorite version of the Myers-Briggs test and started to take it, something I had somehow never done. He stopped me and asked if I had a pen, told me that after talking to me for an hour he was pretty sure which one of the 16 types I was, and wanted to write down his guess before I took the test. He told me not to answer the questions about the version of myself I wished to be, but as I really was. Okay, fine.

When I was done, and the screen delivered my results, I uncrumpled my neighbor’s stickie note and read the same four letters as were shown on the screen. I was impressed, and also felt a little exposed. He went on to tell me about how my type affected my work life, with eerie accuracy. “You'd be a good teacher if you weren't so disorganized,” he said. “I am a teacher” I laughed, a bit embarrassed, “and I am disorganized.” He explained that since I never liked to do anything twice, I was creative and interesting, but I made mistakes and was less effective, and teaching took a lot out of me because I never got the benefit of reusing material. At that point, I was like, “okay dude stop 100% accurately explaining my faults, I would just like to watch the new J. Lo movie and eat my free Popchips now.” But I am not one to turn down free therapy, and his framing, like my brother-in-law’s, was a helpful one. I'm not just undisciplined because of everything that's wrong with me, but a lack of discipline is one side of some of my most special coins. I can always think of a new way to do something. I never settle for monotony. I may not be able to get up and write every morning at 6:00 a.m. (or go to boot camp, now that I have kids), but it means my writing life is full of excitement and spontaneity, and that when I want to write, I write hard. I thought about how to harness these traits for good, not evil. Maybe with a little embedded newness, a little flexibility, I could make something like a regular exercise routine feel more like a creative challenge and less like a maximum security prison.

Of course, life intervened. Three days after the flight east, we attended my niece's bat mitzvah, which was most decidedly lit, and everyone around us got covid. Trips to France were cancelled. End-of-year school celebrations were missed. People showed up in other countries, got sick immediately, and had to go into quarantine. My dad, who I'd made some kind of deal with whatever vague gods may or may not exist to protect, got hit. And all of a sudden, instead of spending a week at our family’s happy place, a small 1950s bungalow on the South Shore of Boston (referred to locally as the “armpit of the Cape”), we were alone again, just the four of us, waiting to see if our April covid infections would protect us, but too nervous to be around the covid or the most vulnerable people in our family. This was also a sweet situation in many ways, but not the one we'd been gunning for, and certainly not the one that would allow for all the independence we’d imagined: our kids playing on the beach with Grammy while we wrote brilliant prose, hours lying around reading old New Yorkers, two nights in the country without our children, and naturally, daily exercise.

A few months ago one of my favorite writers, Hanif Adurraqib, wrote a delightful and moving piece in the New York Times Magazine music issue (one of my favorite magazine traditions) entitled “The Delicious Misery of the Sad Banger.” These songs—ones whose sonic momentum kept us dancing but whose lyrics let us express our anguish—had gotten Hanif, and, he claimed, a lot of us, through the pandemic. In my beachside covid quarantine, in that all-too-familiar feeling of being both tenderly and exasperatingly stuck with my nuclear family, I returned to this article, and to Abdurraqib’s accompanying playlist “Sad But Still Dancing.” “We are all suffering from a prolonged hunger,” he writes, “and the realities of our circumstances won’t let us be satiated.” At the beach, in a space that I would not describe as by any means tragic (we never ended up getting sick), but feeling exhausted by the ambient disappointment and rejiggering of the past few years, these sad, cathartic songs kept me company again. Their comfort shored me up, like the periodic cowbell in Robyn’s “Dancing On My Own,” which Abdurraqib correctly refers to as the “ultimate sad banger,” and which my four-year-old daughter has taken to singing to herself on the toilet lately (parenting win).

There are way more important things than my disappointment. But I am tired, tired of all of this, though I've gotten pretty good at it. A friend said the other day she wasn't sure how she felt about having this skill, knowing she can hunker down with her kids so well, how to push through the difficulty of it. It is so familiar by now, and when my children weren’t fighting over what was clearly a toy designed for a baby, which neither of them sincerely wanted to play with, or screaming about their “legs not working anymore” and needing to be carried to the bathroom, it was quite lovely. And the other times, I wanted to bang my head against the wall.

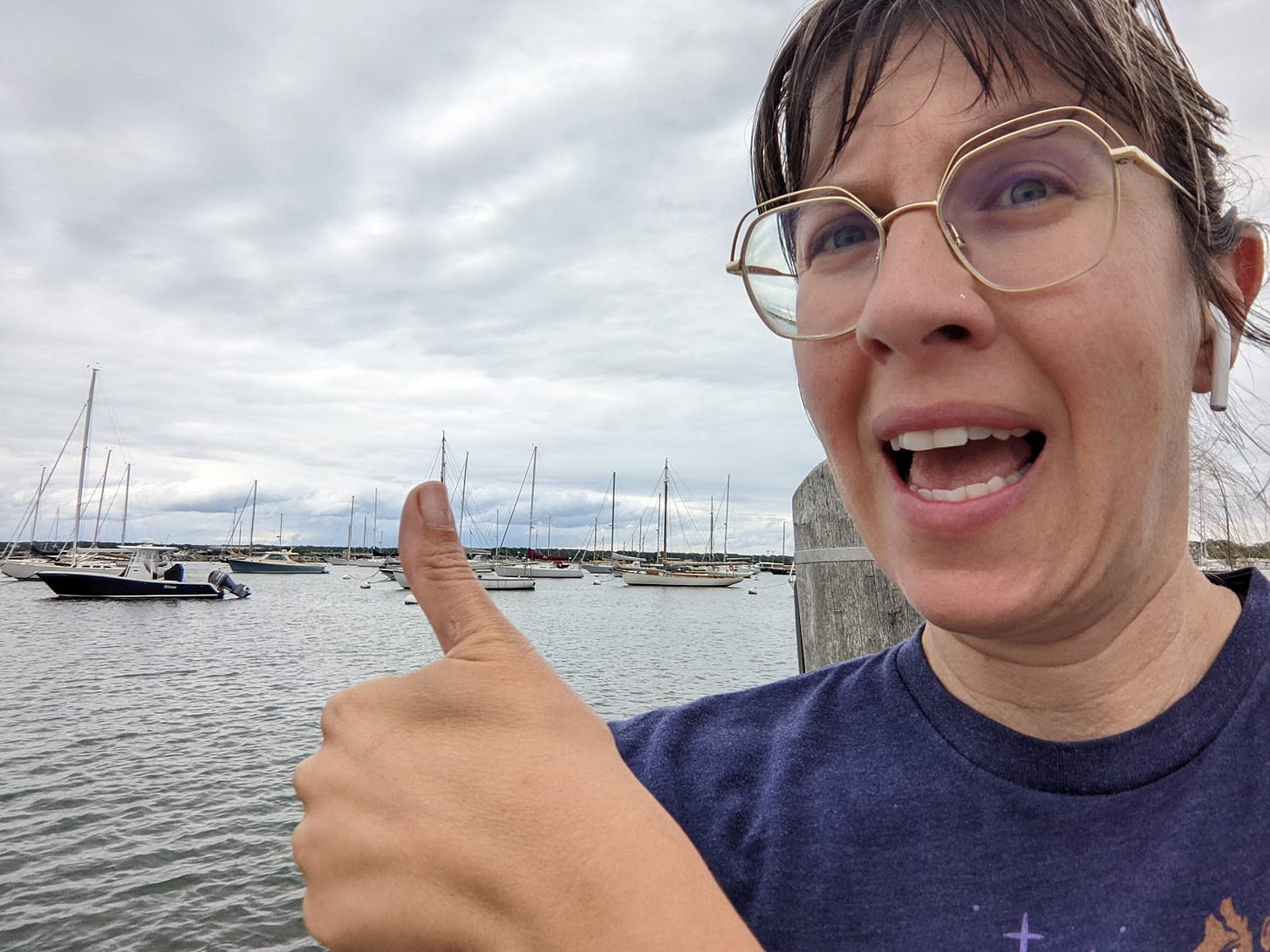

But, armed with music that fit my mood, I did indeed make use of my running shoes. Maybe I've been 60% with my two-mile promise—a bike ride with my son here, a beach walk there. I listen to my “sad exercise bangers,” which I’ve started compiling on my own, having realized that I have loved this exact kind of song for a long time. And, when I remember to do so, I speed up on the chorus. Not fast. Not something anyone would call a run. But enough to make me sweat and feel slightly accomplished. Often I'm so distracted by my own thoughts I forget to do these intervals. Sometimes, like in writing this piece, I stop moving completely to dictate gibberish into my phone. But that is movement too, moving something, like water and sweat, but also moving forward, processing to make room for other things. When my husband told me one morning to “enjoy my run” I successfully kept myself from snapping at him about how I didn’t need his judgement-filled terminology imposed on my low-pressure dabbling in light-heart-rate-acceleration. I think it is possible that even this half-assed attempt at a half-assed routine is having a positive effect on my emotional state.

And there is something else about moving slowly, about trying to do a daily activity that so many people find doable but struggling to be disciplined about it. When I move at a slow pace, I notice a lot of delightful things, and get to go on tangents that might otherwise disrupt a ten-minute-per-mile pace. I can take a few pumps on a swing set, check out the books in a lending library, people-watch. With these excursions, I am not doing the same thing more than once, but it has its benefits. I am burning fewer calories, sure, but I return with my little extrovert heart all full.

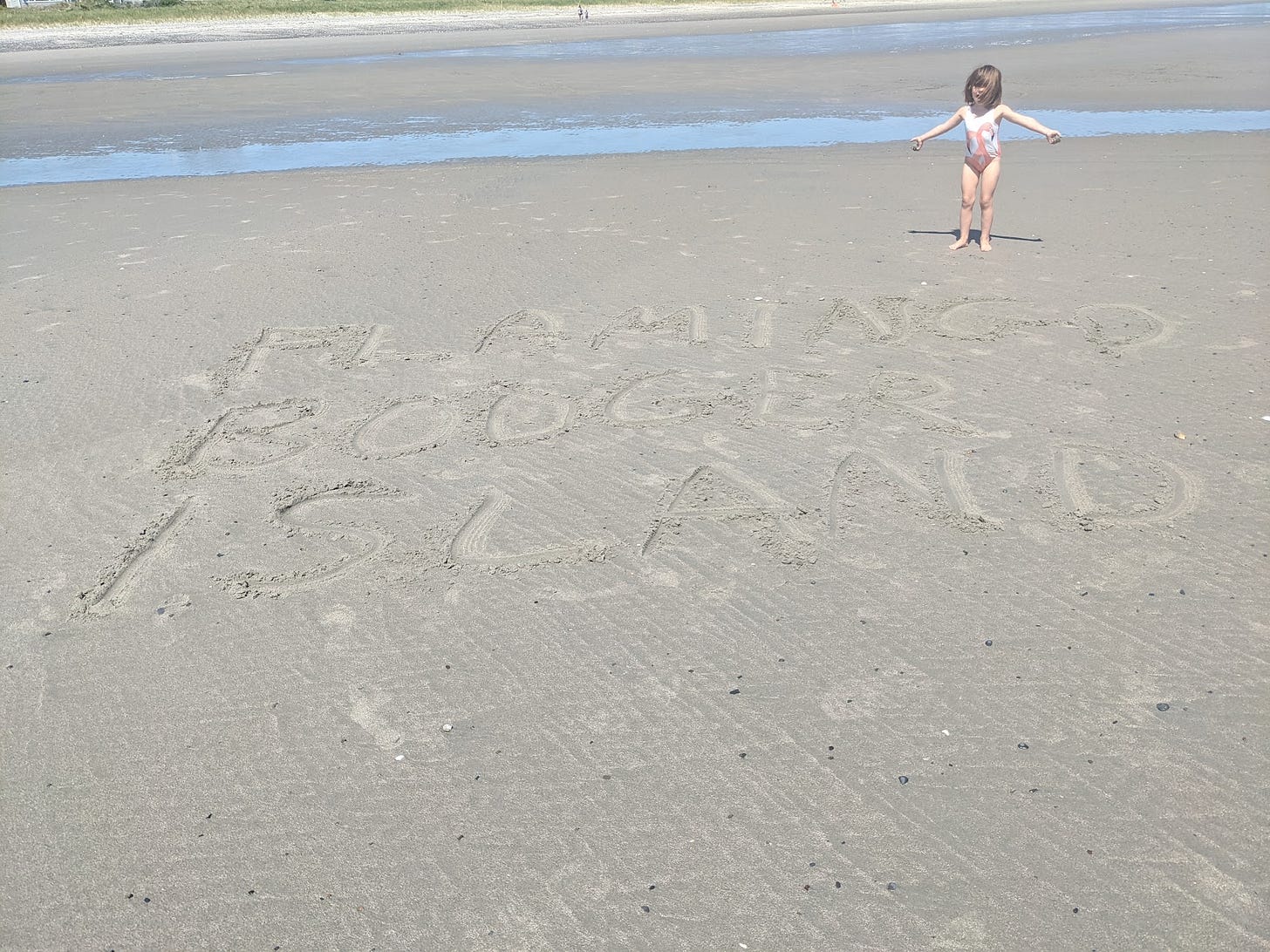

Once my family was sufficiently tired of being apart and the risk of covid seemed sufficiently low, my mom and step-dad came back to the beach for about 36 glorious hours. My husband napped. I turned a 90-minute phone call with an old pal into a long power-walk-slash-wine run. My daughter finally had someone to keep her company on “Flamingo Booger Island” (see below).

I made my own playlist. One I am calling “Sad But Still Jogging Slowly.” If you are sad, too, I hope it provides some release for you. If you don't think you're sad, and then listen to these songs and feel something tighten up deep inside of you and then explode, shattering your facade of togetherness, sorry I started shit. If you want to exercise, but not too much, this might be the playlist for you. If you are enjoying your high-intensity workouts, I am sincerely happy for you and offer you something for your cool down, perhaps. If you never want to move an inch, or set a goal, or make a plan in this time of totally endless disruption, I see you, and I still think music might do something for you from your seat on your emotional or physical couch.

If you are just embarking on your summer vacation (what’s up east coast fam, who for some reason get out of school like a month after Californians), or feeling wary of the July trip to Belgium you planned, which you thought would be so easy because all of the beer and cheese tasting was outdoors, but now there are no masks on planes and airports are going batshit crazy and it’s disorienting how everyone stopped trying to stop covid at the same time that it infected literally everyone you know, I feel you. The health risks are hard to gauge. I worry about my dad, about the other elders and littles in my orbit, about the random 10% of us that may still suffer from long covid despite it only feeling ‘like a cold’ now.

I am not making a pronouncement, but I will tell you that the bat-mitzvah party, where everyone got covid, was absolute heaven, that I still think about it and smile and look at the pictures and say “I’m so glad we did that.” It was on a boat, on a perfect Boston day, and the middle schoolers seemed appropriately self-conscious but also totally willing to embarrass themselves. Even the boys danced together holding hands. And my children happily ate the sliders being passed around on trays by a very nice young lady who told us she’d be going to dental school soon, despite the fact that the sliders had, at one time, touched an onion. The five-year-old daughter of a friend I hadn't seen in ages totally picked up the Macarena in two minutes, a feat an indoor kid like myself never could have accomplished and that was beautiful to watch. I felt like a stone-cold-fox-auntie in my white jumpsuit, and somehow the miracle of no child, or me, which was the greater risk, staining it, felt appropriate for the day. When the last song played and everyone reluctantly shuffled off of the dance floor, the DJ, thick with Boston accent and ruddy with hard living, gave a not bad approximation of the words “l’shanah tova,” and then spoke the holy phrase “Go Celtics!” Even though it ultimately brought some sadness, the party was an absolute banger. Maybe wishing for the latter without the former right now is complete hubris.

-You can find the Sad But Still Jogging playlist here.

-You can find out your Myers-Briggs type here (I’m an ENFP), though I can’t supply a stranger to interpret it for you, sorry.

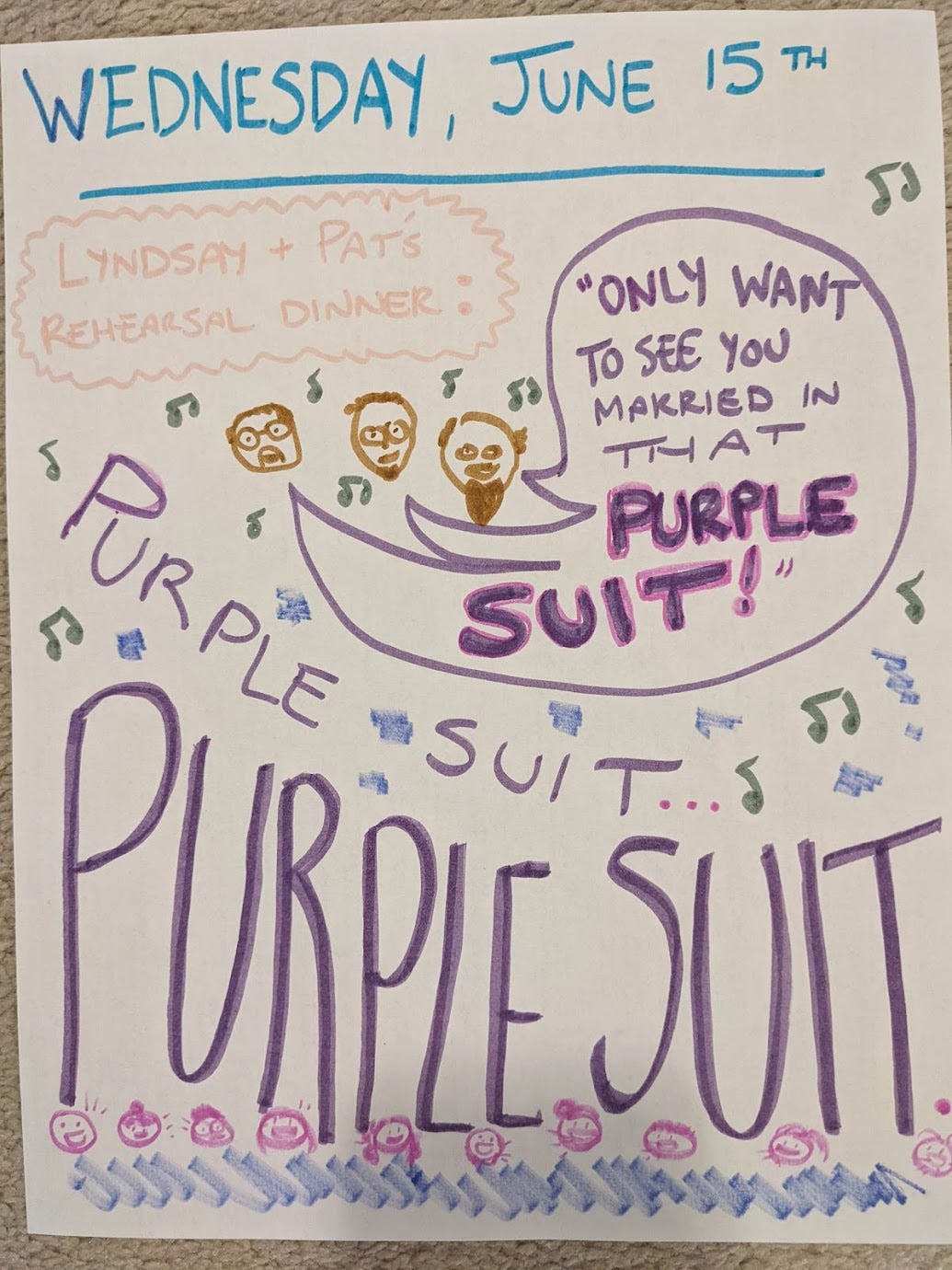

Also, this:

I’ve been doing Austin Kleon’s one-page diary activity (not daily, obviously, but like, twice, which is not nothing!) and it’s really a great way to spend ten minutes. I made this one depicting the rehearsal dinner for my dear friend’s wedding which we miraculously made it to last week, wherein the groom’s family sang a spoof of Purple Rain about the groom’s choice of wedding garb:

Loved this so much and stealing your playlist!

Your title made me think of a quote from Adrienne Martini: “Running very slowly while crying is still moving forward.”