Sibling Rivalry, Revisited

Why can't I reward my kids for getting along?

In this post from what some people would call “last July” and I would call “at least 400 years ago,” I wrote about sibling rivalry. First in my own family of origin, where the animosity between my self and my older brother inspired him to program a computer game that had me, in the form of a giant turkey, as its boss, and then in my now family, where my children primarily refer to one another as “poopy head.”

Like most parents that look back at their own anxiety in a long-gone parenting moment, I can’t believe I was worried about that shit. Not because it wasn’t worth worrying about, but because since then it has gotten SO. MUCH. WORSE. that the major-league sibling conflict curveballs we are currently being thrown make the woes of the past seem like me-participating-in-PE-for-the-fewest-possible-minutes-underthrown-softballs.

Even a few months ago, I would have said that my children mostly enjoyed one another, but lately, it seems like every day is just one long screaming match, punctuated by a sock to the face here and there. My husband and I have spent endless hours, with and without our children, trying to shift this dynamic, with mixed success. We broke down and signed-up for a parenting workshop focused on building sibling relationships, where we expanded our perspectives, tools, and language around it all. It was rad. The course was founded in Positive Discipline, a parenting approach that yeas building relationships, connections, and self-worth in children and nays rewards and punishments.

We learned to think of sibling rivalry as natural and even, gasp, an opportunity for kids to learn how to be in relationship with other people. The goal, we were taught, is not to stop kids from fighting (and in fact, you should butt-in as little as possible). If you coach kids effectively, tell them you believe in their abilities to problem solve, and refrain from shaming or blaming, things still wont be perfect, but you’ll be doing well by the Positive Discipline folks.

I love approaches like this one. From my years of working with kids, I have learned that they are much more capable than we give them credit for at understanding and solving their own problems. You’d be amazed how often, in a classroom, you can tie yourself in knots trying to get little Ginny to participate or look at the board or raise her hand first, but when you actually sit down and ask her, she’s got a pretty great explanation and even a sound solution. I’ve seen kids mediate each other’s disputes, suggest changes to the classroom that us inflexible adults couldn’t envision, and thoughtfully discuss the likelihood of an all-knowing God. I am all about anything that gives kids agency and helps adults see children as resources for resolving conflict, rather than just the cause of all of our problems. My dad, a child psychologist himself (yeah, I know), refers to the places where we can practice messy things without judgement or fear of abandonment as “safe labs.” In a remotely functional family that is free of abuse, home is the safe lab for experimenting with all kinds of nasty behaviors, and one of the essential goals of parenting is not to reject your child for trying all their new routines out on you and their siblings before they take them on the road, but to validate their mistakes and gently give them feedback.

Using the tools we gained from our workshop, we established a secret code for one things are going to far (“Stop Mac n’ Cheese” - see, kids have great ideas!), stopped rushing in to solve minor squabbles, started using more child-empowering language like “what do you both need to do to figure this out?,” and had a surprisingly productive, positive family meeting where we (mostly the kids) generated family rules and made a poster with possible choices for solving conflicts (“do something else, share, say “it’s okay,” take space”), complete with pictures drawn by our five- year-old. We also made sure to give them each as much time on their own as possible - outings with just one parent, a little tent in the living room for the three-year-old to take refuge, space to be seen as individuals and breaks from the intensity of siblinghood.

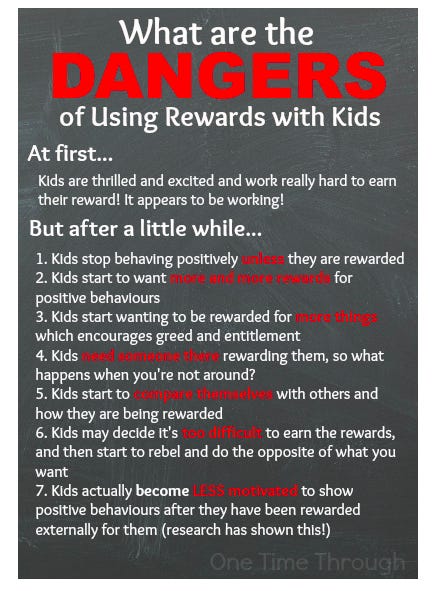

Things were going better for a while, until they weren’t. It was time, for me, to start thinking about the B-word: Behaviorism. Like many educational and parenting philosophies that were born in response to the brutalities of behaviorism and the adult-centered parenting of the 50s and 60s, Positive Discipline has a zero tolerance policy for rewards or any behavioral systems. They believe that rewards teach children only to do things to gain approval or stuff, and that in the long run they wont do these things unless they are rewarded and wont develop an internal sense of motivation. To be sure, behaviorism is rooted in some stinky shit. It smacks of exploitation, power imbalances, and at times, sadism. A lot of bad things have happened to mice, pigeons, and many many humans in the name of behaviorism. There has been some very interesting debate, mostly coming from the autistic community and their allies, decrying the use of behaviorist principles with autistic people, especially children. Also, one time B.F. Skinner (the O.G. of behaviorism) was super skeezy to my mom at a dinner party. So there’s that.

I’m too am very skeptical of purely behavioral approaches. I don’t like conducting Functional Behavioral Analyses of children. I get a little squeamish at the idea of enforcing most any kind of punishment with my children. I believe, wholeheartedly, in Ross Greene’s (another behaviorism-hater who I admire very much) adage that “kids do well if they can.” Shaming them into compliance is not only inhumane, but ultimately ineffective (though it is very, very difficult to resist giving your kids the “why are you doing this to me???!” treatment).

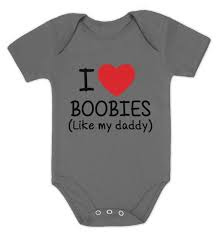

But how I feel about almost everything in parenting and education is, nothing is probably as extreme as we’re making it out to be. Sure, the idea that kids should not be taught skills or loved unconditionally, but only rewarded and punished into some kind of ableist automaton is reprehensible. But, there is no great body of research telling us that the only way to raise healthy, shame-free adults is to never ever ever give them a sticker for brushing their teeth. There are some studies that show some things, but raising little people is complicated, families are complicated, and we’re not telling the whole truth when we tell people, “never do this one thing or you’ll fuck up your children,” unless it is not wearing a seatbelt or buying your child this onesie:

I think we can be pretty confident that excessive shaming of kids, combined with unreasonable expectations, will have some negative psychological impacts. But I don’t think if you went around asking every adult with a good self-concept and interpersonal skills if they never had a chore chart or got a pizza party for reading 10 books over the summer, you’d get a consistent answer. I teach my student-teachers to think of rewards as “habit-helpers:” when someone needs to kick a bad habit or start a new good one, it makes a big difference, in addition to lots and lots of teaching and modeling and practice and patience and love, to help them over that hump.

Practicing new things is hard. I, for one, work very hard not to yell at my kids. I work on it in a meaningful, relational, way. I talk to my therapist about it, practice breathing. My children know I am working on it because I love and respect them, and I apologize to them when I slip up. But would it help me remember not to yell if someone gave me an adorable, super-fun sample-sized lipstick (tiny lipsticks are my “love language”) for every day that I refrained from yelling? You bet your ass it would! Would it help me feel proud of the work I’d done while simultaneously updating my make-up game? Yes yes yes. Would it make me feel deep deep shame if I didn’t get my adorable little lipstick one day? If I was scolded or my name was up on the board with an X next to it, probably. But not if people were chill about it and gave me lots of loving opportunities to try again.

I don’t think parents need to be given more shit about how what they are doing is harming their kids, unless it is abuse and neglect. I want my kids to be respected. And I also want experts to respect my ability to use a range of parenting strategies thoughtfully, based on what I know about my own children. Many blog posts like this one discuss the damage rewards do to children (the author Alfie Kohn’s work is all about this, and again, is lovely in a lot of ways). This author suggests that rewards are like candy - a little bit is okay but you don’t want too much. I like the flexibility of that - but also, I would challenge, for most kids, is more than a little candy really so bad? Haven’t we all, major issues aside, made a little too big of a deal out of candy? Perhaps rewards, like candy (see how I’m commandeering this metaphor here??), have been vilified to the point that parents (and children) are excessively confused about how they should feel about them. Perhaps most kids could eat candy, yes I’m gonna say it, EVERY DAY, and, in the context of a whole lot of other protective factors, be a-okay.

Yesterday, we had a particularly rough morning and morale was real low. When I picked the kids up from school and congratulated a little classmate for newly becoming a big brother, my daughter offered “my brother is mean!” Oy. I called my little brother, with whom I have a lovely adult relationship despite us having definitely been rewarded for not fighting, and despite the fact that no one continues to reward me for getting along with him. My bro, a child psychologist who has done a lot of work teaching parents how to respectfully and effectively use positive reinforcement, had great ideas. All of them were helpful and seemed loving. He mentioned Ross Greene’s Collaborative and Proactive Solutions, a fabulous, behaviorism-free approach to working with children on solving problems. And he also mentioned stars and stickers, those dirty devils, and the idea of reinforcing the skills my children know well but have gotten out of the habit of using.

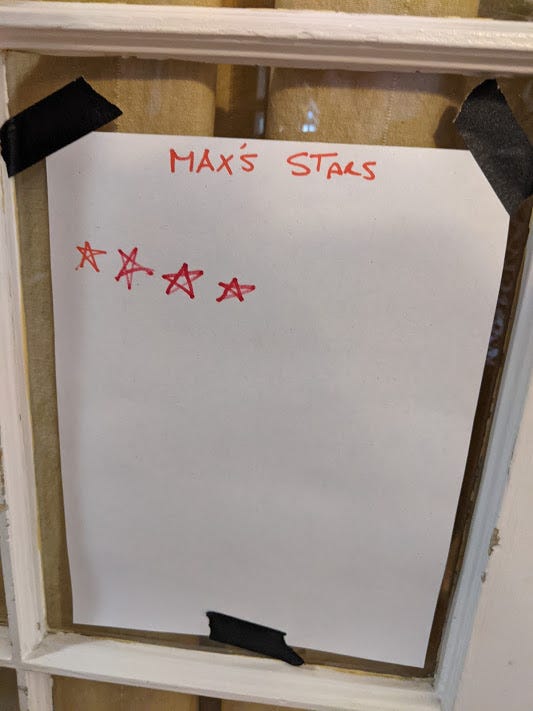

This morning, we offered the kids “challenges,” a period of time in which, if they could meet their goal (five minutes of inside voice for the little one, 10 minutes of no hitting or teasing of the big one), they received a star, to be added up towards some as-yet-decided-on gift. We presented it lightly, we gave lots of reminders and support, and they could could restart the timer if they hit a snag. They both did great - through breakfast, play time, even getting ready and getting to school. It was, no exaggeration, joyous. Instead of keeping them from annihilating one another, we got to laugh our asses off, the whole family, taking turns reenacting last night’s delightful experience of our five-year-old sleep-walking, thinking our bed was the bathroom, and pissing all over the floor. We had a blast, we got along. The stars weren’t the only ingredient - my husband and I reminded each to slow down and bring a light attitude to the morning instead of snapping at everyone, we gave our kids lots of physical affection and attention, we listened to their requests (after a collaborative conversation the night before) not to act so “worried” about them getting dressed fast, but give them some space to do it. Some would say this won’t last and it will damage their intrinsic motivation in the future. I say that’s a bit much, it’s just a few stars on a piece of construction paper in a family where everyone is really just trying their best.

We will make it easy for them to get whatever reward they choose - whatever happens, they deserve it. The message, I hope, will not be “the only thing that matters is pleasing other people and gaining material goods, and by the way you’re only as good as your ability to gain these tokens” but rather “getting along, all the time, in the same goddamn preschool class, in a small apartment, in a pandemic, when your sister yells all the time and your brother is bigger and smarter than you, is friggin’ tough. We’ve all been doing a lot. Thanks for trying. Now enjoy this Lego set of Anakin’s home on Tatooine/stuffed animal version of the deer fox from the Netflix Animated show Hilda.”

I don’t know what will happen tomorrow or the next week or six months or twenty years from now, but the great Ice Cube has taught us that just one good day, especially in the midst of difficulty, should be celebrated. Today I am celebrating this momentary peace, and my freedom to make the parenting choices I want to make, seatbelts on.

-Do you have your own reward examples or sibling battles? Do you totally disagree with me??Leave a comment, I love them all!

Hi Sarah-- I'm not sure if you will read this but I wanted to let you know that I absolutely love these posts and they are incredibly well written and have been a Godsend in my first year of parenthood (which happened to coincide with a global pandemic). Thank you, and well done! -Amira (Esposito aka Booth-Soifer aka Raphi's sister aka That Tall Girl)

I try to give verbal acknowledgment. Saying “I notice you sharing with your sister.” But then I follow it up with “you must be so proud of yourself.” Ive kind of convinced myself it’s striking a balance. Because no we shouldn’t only do a good thing if we get something out of it but, maybe it’s alright to do a good thing because it makes us feel good about ourselves. Also, where do I sign up for this “no yelling gets you free makeup samples” thing? Because I’m in.