Two weeks before my 40th birthday, my brain flipped inside-out. To be more specific, I had an attack of vertigo—one moment staring at the computer screen in my barn-cum-office—the next moment, looking at the floor. I had never experienced vertigo before — my main reference was Liza Minnelli, or Lucille 2, in Arrested Development (Buster to Lucille: “How is your nausea? I mean our…our nausea??”)

I spent the next few days kind of dragging myself along through my schedule with a woozy, confused inner atmosphere. A few days later, it happened again. Then I was, save a Herculean rally to attend my husband’s birthday dinner, in bed for over a week, unable to lift my leaden limbs to do much more than piss, my body heaving itself onto the toilet, holding on to the side of the sink to lug itself back up.

I went to urgent care. I zoomed with my doctor. I tried to keep the emotion out of my voice when I asked her, despite my own embarrassment about the immaturity of the question “will I make it to my 40th birthday party???!” I thought she might consider saving me if she knew I had a big event coming up. She answered yes. These were just some freak symptoms, brought on by a cold, that would leave as the cold did, after a few days of rest. “Treat yourself like you’ve got the flu,” the urgent care doctor recommended, “stay in bed and let your husband take care of things, and you’ll be dancing by Friday night.”

I did not dance. No one did. Well, someone was dancing, somewhere, bless them. But, despite a few days of feeling relatively normal, I was back under my heavy quilt, worse than ever, feeling tremendously sorry for myself, wondering how the world, full of people who were indeed insisting they loved me and sending their regards, could leave me behind. Why were they not standing vigil, candles in hand, on my stoop? How had the universe done me so wrong, and not even bothered to locate Eras Tour tickets for me as concilation?

I went to the acupuncturist, he said it was stress and gave me two bottles of grey pellets that looked like rabbit turds and would supposedly make me feel “amazing” after just a few doses. Another acupuncturist said that, according to Chinese medicine, this was “phlegm wind,” something trapped inside my head that had to be coaxed out. He listened to me with so much care that I was overwhelmed.

The vestibular physical therapist told me, without a shred of doubt, that I was having vestibular migraines. “But, like, for over a month??!” I asked. “Sure,” she replied, handing me a one-pager on prevention and returning to her computer screen. When I asked about how you stop a month-long cluster-fuck vestibular migraine, she replied “Oh, you’ll have to ask your doctor about that.”

I texted my friend the family doctor. I had my neighbor, a pediatrician, look in my ears when they started to become sensitive to noise, a new, unwelcome symptom. I called my step-sister’s husbands daughter-in-law, a neurologist, who suggested steroids. I took those, happily, speedily. I drank Chinese herbs. When a doctor I consulted mentioned that she just read a study that showed people who took a zillion mg of ginger a day had fewer migraines, I stocked up on that. I felt like I was in a never ending loop of “Closer to Fine,” going to the doctor, drinking from any fucking fountain I could find, with my progress most certainly “pointing in a crooked line.”

Most days, I could not rouse myself with less than ten hours of sleep. On a good day I could walk around the block, not without fatigue. Sometimes people would say, “you seem normal!” though I knew I was not. Sometimes they would say, “what the fuck happened to you?” or “I love you but you look like shit.” I could not read or look at a phone or computer for more than a few minutes, usually, without becoming ill. I met my existing freelance deadlines by side-eyeing my screen, taking several Ativan, and begging my husband to pre-edit my incoherent sentences.

I made myself a Meal Train. I cried tears of gratitude while my friends emptied my dishwasher or hung up my clothes in the closet. One friend brought her two children and dinner over, and fed my children too, and cleaned up, and was cheery, and didn’t fuss over me but didn’t assume I would be even remotely helpful. My husband, who had been caring for both my children and me for weeks and weeks, nonstop, with few complaints, went out to the movies. I truly thought that night, looking at my friend as she tidied up the play ice-cream-stand and scraped plates, that I’d never come closer to divinity.

Another neurologist, the kind of little old guy you want as your doctor, examined me with a somewhat mystical air and pronounced me migraine-less. “You had an everyday virus” he explained, “which went to your brain. Now it is gone, we cannot fight it, you can only heal.” This was, it seemed, both the same thing those early doctors had said and very, very different. No one had ever suggested to me that an everyday virus, not meningitis, not a power-house one, could just mosey on over to your brain and fuck some shit up. He told me an MRI would probably show nothing, but, he added, “We do MRIs for anxiety.”

I didn’t think he needed an MRI to confirm my anxiety.

Then I realized that he meant he could give me one to ease my worries. “Yes,” my husband and I responded, in unison. We’ll take one of those.

We’re all deeply familiar with FOMO. The minimalists, the good folks among us who want to intentionally attend rather than letting their precious life minutes fill up with garbage, have recommended JOMO (Joy of Missing Out). At the beginning of this thing, and still in waves, the FOMO was real. I missed many celebrations— a wedding, birthdays, concerts. I missed my weekly hike up a local mountain, taken almost religiously for years with friends I hold dear. I missed deadlines. Missed income. I missed making my kids breakfast, taking them to school, volunteering in their classrooms, connecting with other parents after drop off. I missed reading my son Wildwood, which we eventually found on audiobook, but it wasn’t quite the same. I suppose it was just, MO, actually, just the everyday fact of actually missing out. I moved past the fear into a new reality.

I now find myself with something I might call ATMO - Accustomed to Missing Out. There is some peace in it, like many of us found at some point during the pandemic, if we were lucky enough to be spared acute and everyday pain, or even, alongside such a thing. My world is just…smaller. Some days are bad and others are better. Sometimes I start to think I am people again, make a dinner plan. Try to imagine the book I want to write.

Even the language I have used, am using, to describe what is happening to me is curious, telling, about what I, we, expect of our bodies and lives. I have learned to stand by my right to be upset, to feel a bit let down by my doctors, to grieve for my own disappointment and pain, to let it not be relative to the greater bodily dangers and pains of others. But some of the best advice I’ve gotten, from a friend who spent the greater part of a year recovering from a concussion that still impacts her, is not to hold returning to my former self as the prize for my journey of healing. This is me, now. This is still my brain. I think of what I teach children, that no brain or body is better or worse than any other. Of course I want to write. I am dying to take the subway into the city, walk to the modern art museum, stop at the cafe, carry my bags, come home exhausted but energized. But there are many ways to spend a day well.

Another take on my condition, from the intuitive healer my family and friends often go to in hard times (yes, I know, but don’t knock it till you try it), is that I am simply having a “spiritualized temper tantrum.” My star chart shows nothing but doors opening before me, but my cards are all resistance, ambition upside-down, a monumental holding-back. There is something I have to grieve, she believes, before I can move on to the next 40 years, walk through those doors, not like an errant virus but perhaps like a cure for my decades of angst and ambivalence.

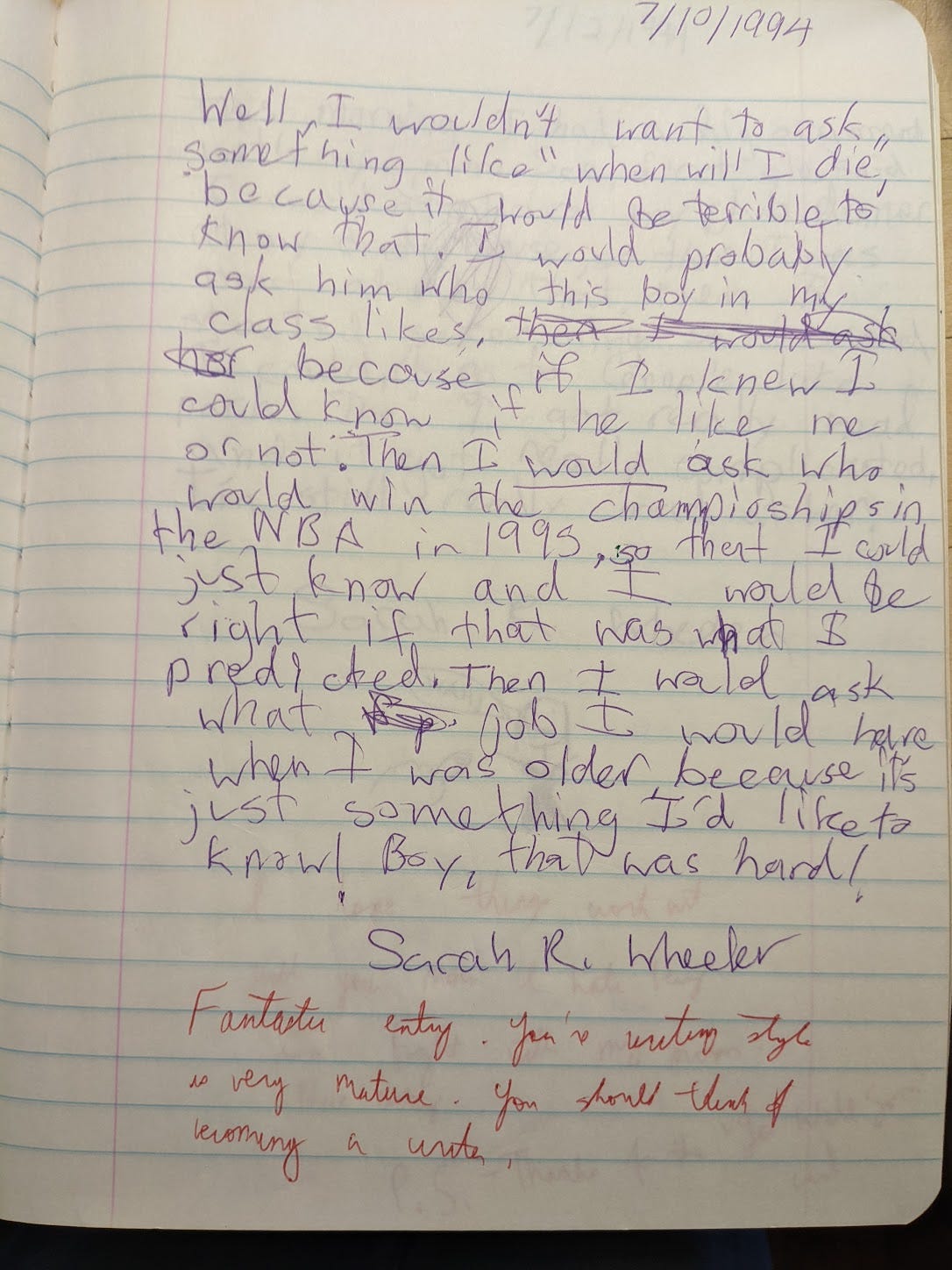

There is a literal large box, still taped shut and sitting in a corner of my bedroom, stuffed with my childhood journals, freshly uncovered from my mother’s basement. The intuitive explains that all I have to do is read through them, is ask my childhood self, “what do you need me to know today?” and the spell will be broken. She’ll let me go, no longer afraid that I will leave her behind without properly mourning her.

“But I’ve spent my whole life taking care of her!” I complain to my therapist, who has been begging me to converse with my little girl self for years. A pause. The sound of hesitation. And I realize I’ve misunderstood. I wasn’t caretaking, I was running away.

In one of my childhood notebooks, a teacher asked nine-year-old me what I would do if I had a chance to consult the oracles of ancient Greece. I respond that I wouldn’t ask when I will die, because that would be a terrible thing to know. Better, I write, to know who has a crush on you, or who will win the next NBA championship. Or, I suggest, maybe I’d want to know what job I will have some day? “You should think of becoming a writer,” my teacher scribbles back to me. Perhaps I can still run back.

When I told all of this to the MRI technician, yesterday he was unimpressed! Just kidding, I didn’t go into the thing about mourning your childhood self, but I did tell him that I managed to get through my claustrophobia and endure his awful, brilliant machine by thinking about every single person I loved. He nodded politely, ready for his long day to be over I imagine, and in my head I said “I love you too, technician guy, even if you don’t love me back.”

What is the work of recovery? Our AA friends would tell us it is never-ending, even if the final step is complete spiritual awakening, it is not truly a resting place, but an offer to keep going. What if we never go back to our old selves? It would be sad, but not all bad.

In an essay about her disability on her Substack, Rising and Gliding, Erin Ryan Heyneman talks about her own belief in her body and brain’s ability to grow and heal, about the power of that faith, about her gratitude for how much she has improved from her lowest points, and also about the discomfort of favoring an able body over a sick one. “Today I am about seventy percent physically “better,” but I’m completely changed as an individual,” she says. There’s a lot of misplaced hero worship in our narratives around disability, and overcoming illness. But there is also something forever altering about losing the version of yourself you thought you’d always have, and learning to love the one you’re most literally with.

The naturopath thinks my adrenals are wonky. The chiropractor thinks if I just stop jutting out my right hip my skull will rest easier. The cranio-sacral therapist thinks that my brain has a lot it wants to tell us, and we just have to listen, which I started to roll my eyes at before I realized they were absolutely gushing tears of recognition.

I think I would like to have the energy again to wake up before my children. To be relied upon by them. I think I’d like to write, for hours, my mind whirring like it used to, like it does in small glimpses, like it may or may not again.

I also think I wasn’t perfect before this happened. I spent the first month of my illness grieving that no one was coming for me. Now it has shifted to something more like “no one is coming for me but me.” I am writing down notes so I don’t forget to ask the questions I meant to ask. I am reaching out for help. I am, I think, a bit more patient, even though the way I got here is not, as my young niece used to say, my favorite.

Also, this:

Things I listened to with joy over the past few months:

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. Smart and enthralling!

Lindy West’s insane and brilliant movie reviews, compiled in the book Shit, Actually. I actually think her “Honey I Shrunk the Kids” review deserves a Pulitzer.

The music podcast Switched on Pop, especially the Kiss from a Rose episode.

This enneagram deep dive (I finally concede that I am a four!).

Things I wrote while in bed drowning in self-pity, but still with love and passion:

‘Motherhood Radicalized Me’ in The Cut, on Amanda Montei’s Touched Out: Motherhood, Misogyny, Consent, and Control

“I’ve been able to let go, somewhat, of the belief that the burden is on me to teach my children the right way to think about everything. I emphasize bodily autonomy and consent; that’s sort of the foundation of how I think about parenting. As my kids have gotten older, there’s a lot that’s not in my control. And writing this book really confronted me with that fact.”

How Gen Z Women Athletes Are Writing Their Own Storylines for Bustle

“The result of both of their social media personas, though slightly different in flavor, is a positive, unguarded, slightly egomaniacal and very female vibe. They don’t have to be “one of the guys” or choose between being role models and being incredibly sure of themselves.”

American Mom Rage Could Fill a Book and Now it Has for Romper on Minna Dubin’s Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood

“I was surprised when I discovered, through interviews with mothers, that mom rage can be internalized. I’m such a loud person, and I naturally externalize all my emotions, so it hadn’t occurred to me that there are lots of mothers out there experiencing mom rage without yelling and stomping! Many are taking out their rage on themselves through self-harm and substance abuse.”

And I’m still plugging away with new installments of The Good Enough Parent, my anti-parenting-advice parenting column! Submit your questions, big, small, well-trodden or risque!

I’m so sorry you’re going through this. Thank you for sharing this. I feel somehow like I can’t compliment the writing without complimenting the pain involved, but it’s a beautiful piece.

I do not want this to be happening to you, not one bit, but I am still honored to be one of your mystery-brain-illness-having friends