Greetings from an adults-only Mexican vacation! It is very relaxing here, I am leaning into that relaxation, spending all day in my bathing suit, never rising from my bed before ten. Today I set my alarm for nine and snoozed for an hour, and I dont care if it’s not quality sleep, snoozing is DELIGHTFUL. My god-sent mother-in-law is back home with our two kids who sent us a video last night of them just singing the word “guacamole” and cracking up. So, I think they’re doing great.

Today I indulged myself in a facial, which, from what I could apprehend, prone with my eyes shut, consisted of being massage by a breakfast bowl. First it was yogurt with salt, then honey, then kiwis — fresh, not frozen, I knew, because I’d seen a dude deliver a bag of them as I sat in the waiting area. Afterwards, the esthetician told me to stay out of the sun. The power of probiotics! Though it was all a bit mystifying, this facial was in sharp contrast to the ones I’ve experienced most of my life, where they rub and steam you into a false sense that you can let your guard down, then whip out a tiny scalpel and florescent magnifying light and proceed to excavate all of your pores while you squirm, assuring you that it will be over soon in a tone that sounds, at the least sadistic and at most, a little turned on.

Vacation is lovely, but the other people on vacation, particularly the other Americans, are challenging. I know I am an American on vacation! I probably suck a bit too, but I can’t help wishing it was just me, my husband, and the unbelievably talented dudes who climb the coconut trees each day to preventively castrate them. This place is a bit like a wax museum of White heteronormativity. Straight, White, cis couples of all ages, sizes, and colloquialisms, being aggressively predictable (but sometimes nice!) Of course, I am also one a terrible fun-house American, speaking in my poor Spanish to people with great English, hoping they will like me as I simultaneously ignore and invoke our very real power dynamics.

In a truly tremendous SNL sketch I just recently saw, Adam Sandler’s tour operator reminds us that if we’re unhappy at home, we’ll be unhappy on vacation. “Same sad you!” the fine print warns.

I am not drinking much alcohol, since I descended into a mysterious and debilitating life as a chronically dizzy person six months ago, and I don’t think I’d ever noticed quite how much booze many people on beach vacations throw back. There are several guests here who trade one just-emptied beer for a newly-cracked one, all day, like a monkey swinging from branch to branch. The bartenders, just doing their jobs incredibly well, ask me in our first interaction of the day, if I’m ready for a drink. I have had many conversations where I couldn’t quite place what was off, until I remembered that some of the people here are just absolutely trashed, all day every day. I do miss drinking, but maybe not like that?

Instead of drinking, I’ve been thinking about the female body. I know, I know. Lighten up lady! You can’t take me anywhere.

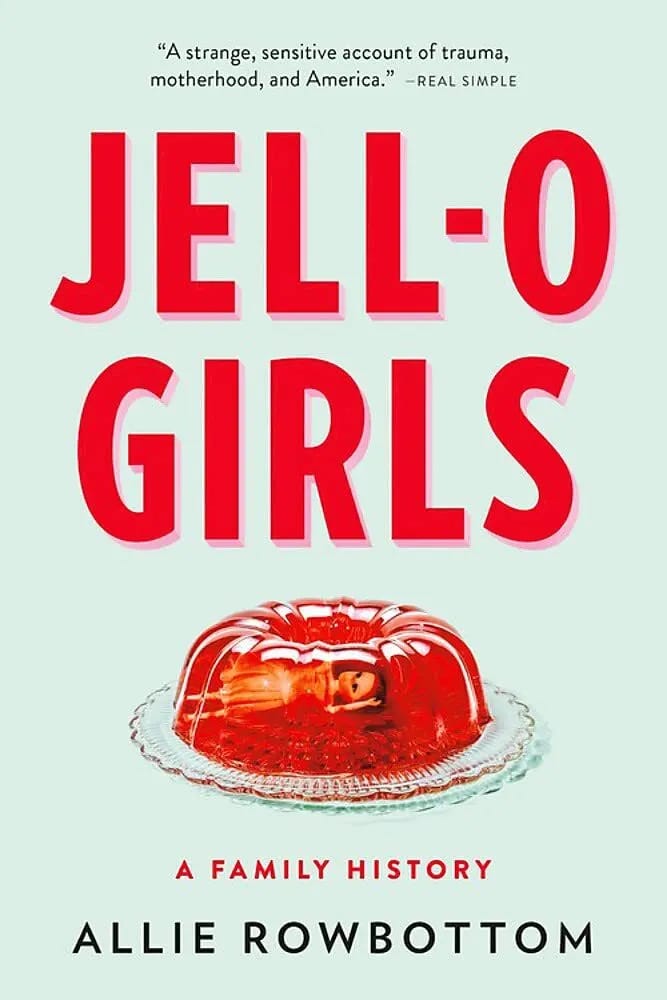

Specifically, I’ve been thinking about the female bodies portrayed in the books I’ve read in the last few weeks — the bodies who suffer from the unspoken or unheard trauma of patriarchy (in Allie Rowbottom’s Jell-o Girls), the bodies who are imperfect and better for it (in Jessica Slice’s Unfit Parent, out soon), the bodies who create and lose and long for and mourn other bodies (in Louisa Hall’s Reproduction and Tamarin Norwood’s The Song of the Whole Wide World, out tomorrow).

If you take these books as their own cannon, they tell wide-ranging tales of the female body that are distinct but adjacent, like several Coronas consumed in a row. I can’t tell if they’ve left me in different places, or all brought me back to the same one: The female body is a wild place. It is often not believed. It is often controlled. What we make from it isn’t just a miracle of biology, but our own will.

In her memoir of her legacy of both Jell-o money and physical and psychological distress, Rowbottom tells the tale of three generations of women — her grandmother, her mother, and herself, and the “curse” that afflicted them all, which turns out (spoiler alert, but not really) to be the pain of living in a society that distrusts you, dismisses you and often actively wishes you harm. She refers to both this harm, and what manages, at times, to protect against it, as witchcraft. She doesn’t want to live in the world that enacts and re-enacts this curse on every woman in her family, but in a way, enduring it, and showing up for other women with forgiveness, is an act of resistance.

Jessica Slice experiences her own curse, at least it seems so at first, in her story of becoming disabled, then becoming a mother, then needing to make sense of how those experiences inform on another, not just for herself, but for others. After an ill-fated adventure on a Greek isle that can only be described as macabre, Jessica, young and able-bodied, falls ill. She spends the next two years trying to convince her doctors that there is something wrong with her (that should not be a point of contention - she can no longer walk or sit upright for more than a few minutes, among other things), until they convince her that she’s made it all up. Ready to admit psychosis, throwing up her hands from all the trying, someone finally suggests a legitimate, non-hysterical reason for her symptoms. Then, she begins the long journey of, having been disabled for years, learning to identify that way. But, unlike Rowbottom, her story doesn’t end in sadness, perhaps because a rich culture of marginalized, actualized people is there to teach her the ways of another kind of living, one where perfection is off the table and she is free to decide what should come in its place. The good kind of witchcraft, I guess.

When I talked to Slice about the book on my podcast (she’s a fabulous interlocutor), she told me that in surveys, disabled people report a much higher quality of life than the doctors who sometimes feel it is humane to refuse them life-saving treatment, or who caution them from bringing babies whose lives will be like theirs, to term.

Reproduction, an auto-fiction-like novel that threads the comings and goings of the narrator’s womb with the story of Mary Shelley, her Frankenstein, and her brutal trials as a mother, is all foreboding. I *love* a tale of female body horror (I have set a Google alert for the words “Nightbitch trailer,” which, if you don’t know, Google it). It’s a small book, and I opened it late last night, and after a bad night of sleep, finished it this morning on the beach. Just as Jell-o Girls and Unfit Parent seem to be two sides of a similar coin, Reproduction pairs neatly with the exquisite Song of the Whole Wide World, another small-but-mighty one.

In Song, Norwood, who was also interviewed on my podcast earlier this week, and whose voice is almost addictive to listen to, doesn’t shy away from body horror as she tells the story of carrying and delivering a baby that she knew would only live for minutes. But she weaves the horror with something hopeful, not because she needs a happy ending but, because, like Slice, who kind of slipped horizontally into a different, in some ways, better plane of existence when she became disabled, Norwood is somehow able to hold the grief and loss and lack of control and pain of the human body, and of motherhood, at the same time as she holds its magic.

I’ve been thinking about my own body, too. I recently found, after months, a diagnosis that I think fits what I’ve been experiencing. From what I understand, my brain, after an initial trauma (a series of vertigo attacks in August), still thinks my body is falling. In order to save us, it over relies on visual information — taking in more than a healthy serving of what it sees, causing me to feel, much of the time, like I’ve just stepped back onto land from a boat ride. It was funny, to read a formal description of something I’ve been saying to myself for months, the boat thing. And to understand why the speed and volume of what I see can make me sicker. (I tried, last week, to watch Jacqueline Novak’s new comedy special, but all of her rapid stage-pacing made my head spin).

My friend asked me if the possibility of this diagnosis, and its potential treatment, made me feel hopeful. I thought what I’d felt was hope, and yes, hope was there, but more than that I felt bogged down by the dread that characterizes both Jell-O Girls and Reproduction, which is a bit about the fear of my own body, but mostly the fear of needing people to believe me about what’s happening in it. I’ve already begun the long, bureaucratic dance of trying to figure out which doctor can confirm what I already know, getting dead-end messages, or dismissive ones, or, and for this I should feel lucky, flummoxed-but-willing ones from the one doctor on my team who seems both able to admit when she doesn’t know something and to maintain some drive to find out the answers. All of this, more than my brain and its over-protective attack on my body, like it is a man with a machete hacking away at a coconut to prevent an disastrous descent, scares me. To make matters more absurd, the Mexican internet does not want me to log on to my health portal. Each time I try, it only displays the word “Forbidden.” Having been up all night reading a book about body horror, it’s hard not read that as some kind of warning. So I am reading and responding to each unsatisfying message from each doctor through my own mother, who patiently tried three different passwords to hack into my medical records, where she screenshots (and often comments with humble encouragement on) all of my messages.

I did take a break from all this to go into the ocean today. It helps that my phone doesn’t work here, well it doesn’t really work anywhere. Like my body, it is very, very annoying, but I do love it, perhaps even more for its shittiness — its broken camera, its app-crashing, its sending of the same text repeatedly or not at all. When I drop it, which is often, another tiny piece of its screen falls out. I love these pieces. I wish them well. I’m proud of them for letting go, and of my phone for hanging on. My friends, my children, remind me that I need a new phone, but this imperfect one complicates my life in a way I don’t want to give up.

At the beach, I inaugurated a skimpy Target bathing suit. When I tried it on at home, my five-year-old daughter declared “This one is…unappropriate. You could wear it around your family, but with your friends, I don’t think it’s a good idea.” I told her she didn’t know all the crazy things my friends had already seen, but I did wonder if I could pull it off. I kept it, and tugged it on over my woozy head, slapped on some hot pink lipstick and tousled my salty hair, looked at my reflection, and thought “you still got it!”

But when I asked my husband to take a picture, for the friends I am lucky to have who insisted I keep it, the image didn’t look like the one I saw in the mirror. I didn’t send the photo, after all, but I still believed what I’d seen of myself. That one, though I couldn’t quite describe it to anyone else, was the real me.

Also, this:

If you haven’t already, watch John Early’s delightful, musical comedy special Now More Than Ever on “Max” (ugh, what a dumb name!). You wont be sorry, and you’ll be able to understand why I keep going around saying “I don’t know WHAT HAPPENED!” all the damn time.

And, P.P.S., we are doing a very fun thing over at the Mother Culture podcast, which I co-host with Miranda Rake. We have monthly “Movie Club” episode just for paid Patreon subscribers, and we just released a tremendous talk with journalist Tracy Clark-Flory about the Oscars and motherhood in the movies this past year, where she gives us her takes on Poor Things, May December, Anatomy of a Fall, and more, and where I pledge to begrudgingly watch Oppenheimer, and buy Tracy and Miranda each a large popcorn if I end up enjoying it! Check it out and join us for more!

Sarah, you continue to demonstrate such strength of character and lively fortitude as you wrestle with the wee beasties that have descended upon you. A temporary soporific for your symptoms whilst staying with this theme:

https://www.vudu.com/content/browse/details/Beach-Blanket-Bingo/140406

Post Script: My college friend Marcia Millman's book is interesting; Such Pretty Face by Marcia Millman

Wow I loved this (and also — not at all!!! but in a good way 😂). I relate to so much of it and this part made me emotional: "...the fear of my own body, but mostly the fear of needing people to believe me about what’s happening in it"

I've been managing chronic illness since I was a baby. It started off with my mom bringing me to any and every health practitioner imaginable (she is my #1 champion! Go moms!), and now that I'm a real grown adult human, the journey has continued with me as the driver. I figured by now I'd have found my person, my doctor, my health provider who cares about problem-solving this with me, but alas!

I've also been thinking so much about my body as so much more than just that, given I have a 10-month-old boy who is still nursing, AND we'd like to try for a second child at some point in the next year. My body has not been my own in ~20 months, and will continue to serve my children for many years to come (if we're lucky enough to have more), and STILL it is a nuisance to the medical establishment. It's baffling, and if I think about it too much, it hurts. I try to stay positive — but my goodness 🙈

Thank you for sharing ❤️